To elaborate on the Magisterium of the Catholic Church is our mission on Plinthos (Gk. "brick"); and to do so anonymously, so that, like any brick in the wall, we might do our little part in the strength of the structure of humanity almost unnoticed.

Saturday, September 27, 2014

The Historical Development of Christian Anti-Cultic "Worship"

Here is an article about the 16th Century liturgical revolution with it's gradual desacralization of Christian Worship.

Right Worship is directed to God and includes sacrifice: offering of a victim by a priest to God alone, in testimony of His being the Sovereign Lord of all things, viz. Calvary! That is the Mass! It should not, it cannot, be diluted!

Friday, September 26, 2014

True Christianity is within the "Walls" of the Church!

Consider this story told by Saint Augustine (Confessions: Book VIII, Chapter II), of a certain Victorinus; a great man of Rome, who at first attempted to deny his need for the Church, falsely claiming to be a Christian without the Church.

To Simplicianus then I went, the father of Ambrose (a Bishop now) in receiving Thy grace, and whom Ambrose truly loved as a father. To him I related the mazes of my wanderings. But when I mentioned that I had read certain books of the Platonists, which Victorinus, sometime Rhetoric Professor of Rome (who had died a Christian, as I had heard), had translated into Latin, he testified his joy that I had not fallen upon the writings of other philosophers, full of fallacies and deceits, after the rudiments of this world, whereas the Platonists many ways led to the belief in God and His Word. Then to exhort me to the humility of Christ, hidden from the wise, and revealed to little ones, he spoke of Victorinus himself, whom while at Rome he had most intimately known: and of him he related what I will not conceal. For it contains great praise of Thy grace, to be confessed unto Thee, how that aged man, most learned and skilled in the liberal sciences, and who had read, and weighed so many works of the philosophers; the instructor of so many noble Senators, who also, as a monument of his excellent discharge of his office, had (which men of this world esteem a high honour) both deserved and obtained a statue in the Roman Forum; he, to that age a worshipper of idols, and a partaker of the sacrilegious rites, to which almost all the nobility of Rome were given up, and had inspired the people with the love of

The monster Gods of every kind, who fought

'Gainst Neptune, Venus, and Minerva:

O Lord, Lord, Which hast bowed the heavens and come down, touched the mountains and they did smoke, by what means didst Thou convey Thyself into that breast? He used to read (as Simplicianus said) the holy Scripture, most studiously sought and searched into all the Christian writings, and said to Simplicianus (not openly, but privately and as a friend), "Understand that I am already a Christian." Whereto he answered, "I will not believe it, nor will I rank you among Christians, unless I see you in the Church of Christ." The other, in banter, replied, "Do walls then make Christians?" And this he often said, that he was already a Christian; and Simplicianus as often made the same answer, and the conceit of the "walls" was by the other as often renewed. For he feared to offend his friends, proud daemon-worshippers, from the height of whose Babylonian dignity, as from cedars of Libanus, which the Lord had not yet broken down, he supposed the weight of enmity would fall upon him. But after that by reading and earnest thought he had gathered firmness, and feared to be denied by Christ before the holy angels, should he now be afraid to confess Him before men, and appeared to himself guilty of a heavy offence, in being ashamed of the Sacraments of the humility of Thy Word, and not being ashamed of the sacrilegious rites of those proud daemons, whose pride he had imitated and their rites adopted, he became bold-faced against vanity, and shame-faced towards the truth, and suddenly and unexpectedly said to Simplicianus (as himself told me), "Go we to the Church; I wish to be made a Christian." But he, not containing himself for joy, went with him. And having been admitted to the first Sacrament and become a Catechumen, not long after he further gave in his name, that he might be regenerated by baptism, Rome wondering, the Church rejoicing. The proud saw, and were wroth; they gnashed with their teeth, and melted away. But the Lord God was the hope of Thy servant, and he regarded not vanities and lying madness.

N.B. The Gospel for today's Mass (Luke 9:18-22) also bears this out, for it is Saint Peter alone (the leader of the disciples--the Church) who recognizes and reveals who Jesus is. The source of this revelation is not the Bible but the Holy Spirit Who moved the Pope, and the New Testament writings were based on that! The disciples first recognized Jesus as Christ (the Messiah) by the revelation to Saint Peter, the first Pope. They got it wrong. Only Peter had it right! Only Peter knew Christ correctly. Those with Peter get it right.

"Lack of Charity"

That is the buzz word accusation, for which the Bishop of Ciudad de Este is suspended, so typical of the abuse of ecclesistical authority these days. There is no apparent canonical crime; but a severe canonical penalty is imposed. The one in authority abuses his authority and unjustly disciplines the one who is vaguely accused of who knows what and then blames the accused for getting angry (and perhaps complaining) about the irregularity involved in his own case and requesting due process!

Since when is injustice less offensive than "lacking charity"? Charity is a gift which might not be given, without any implicit offence. Besides counterfeit "charity" abounds which is often contrary to right worship (cf. John 12:1-6)! Justice is the more basic virtue and the violation of it is a sin, and anyone who is guilty of it will answer before God, as the presumably innocent Bishop has rightly said.

Injustice is the greatest lack of charity!

If my defense and promotion of the honor of God should offend you, that is no lack of charity but actually the source of all charity: the love of God is the essence of charity.

Suspended Prelate Speaks: Communion is in Christian Fidelity!

Not sure how long these gems would be there, I have copied and pasted the entire statements below from the Diocese Ciudad del Este Bishop's Column. Basically this Bishop of the Prelature of Opus Dei who has been leading the diocese for a decade claims that he is the victim of an anti-Traditional reactionary purging under the reigning Pontiff.

Bishop Livieres claims that there is no just cause for his removal (the procedure of which entailed several canonical irregularities) and that his diocese was practically the only oasis of real Catholic pride in the entire country of Paraguay, and it is for that reason that he had been roundly opposed by the (Liberation Theology) status quo from the start and is now summarily removed. Good bye Reform of the Reform in Paraguay, for now!

P.S. Perhaps the Holy Father should be reminded, in his heavy hand against Tradition, of the Gamaliel principle: "Refrain from these men and let them alone. For if this council or this work be of men, it will come to nought: But if it be of God, you cannot overthrow it, lest perhaps you be found even to fight against God." (Cf. Acts 5:38-39)

Carta de Mons. Rogelio al Prefecto de la Congregación para los Obispos

Jueves, 25 de Septiembre de 2014 13:59

Cardenal Marc Ouellet

Carta abierta de Mons. Livieres a la Iglesia en Paraguay. El mundo sufre una desacralización y en nuestro país esto tiene forma de Teología de la Liberación. La comunión en la Iglesia debe buscarse y hallarse en la Eucaristía, único y verdadero signo de unidad.

Carta abierta de Mons. Livieres a la Iglesia en Paraguay. El mundo sufre una desacralización y en nuestro país esto tiene forma de Teología de la Liberación. La comunión en la Iglesia debe buscarse y hallarse en la Eucaristía, único y verdadero signo de unidad.

Bishop Livieres claims that there is no just cause for his removal (the procedure of which entailed several canonical irregularities) and that his diocese was practically the only oasis of real Catholic pride in the entire country of Paraguay, and it is for that reason that he had been roundly opposed by the (Liberation Theology) status quo from the start and is now summarily removed. Good bye Reform of the Reform in Paraguay, for now!

P.S. Perhaps the Holy Father should be reminded, in his heavy hand against Tradition, of the Gamaliel principle: "Refrain from these men and let them alone. For if this council or this work be of men, it will come to nought: But if it be of God, you cannot overthrow it, lest perhaps you be found even to fight against God." (Cf. Acts 5:38-39)

Carta de Mons. Rogelio al Prefecto de la Congregación para los Obispos

Jueves, 25 de Septiembre de 2014 13:59

Cardenal Marc Ouellet

Prefecto de la Congregación para los Obispos

Palazzo della Congregazioni,

Piazza Pio XII, 10,

00193 Roma, Italia

Palazzo della Congregazioni,

Piazza Pio XII, 10,

00193 Roma, Italia

25 de septiembre de 2014

Eminencia Reverendísima:

Le agradezco la cordialidad con que me recibió el lunes 22 y el martes 23 de este mes en el Dicasterio que preside. Igualmente, la comunicación por teléfono que me ha hecho hace unos momentos de la decisión del Papa de declarar a la Diócesis de Ciudad del Este sede vacante y de nombrar a Mons. Ricardo Valenzuela como Administrador Apostólico.

Tengo entendido que el Nuncio, prácticamente en simultáneo con el anuncio que Su Eminencia me acaba de dar, ha realizado una conferencia de prensa en el Paraguay y ya se dirige hacia la Diócesis para tomar control inmediato de la misma. El anuncio público por parte del Nuncio antes de que yo sea notificado por escrito del decreto es una irregularidad más en este anómalo proceso. La intervención fulminante de la Diócesis puede quizás deberse al temor de que la mayoría del pueblo fiel reaccione negativamente ante la decisión tomada, ya que han manifiestado abiertamente su apoyo a mi persona y gestión durante la Visita Apostólica. En este sentido recuerdo las palabras de despedida del Cardenal Santos y Abril: «espero que reciban las decisiones de Roma con la misma apertura y docilidad con que me han recibido a mí». ¿Estaba indicando que el curso de acción estaba ya decidido antes de los informes finales y el examen del Santo Padre? En cualquier caso, no hay que temer rebeldía alguna.Los fieles han sido formados en la disciplina de la Iglesia y saben obedecer a las autoridades legítimas.

Las conversaciones que hemos mantenido y, aparentemente ya que no los he visto, los documentos oficiales, dan por justificación para tan grave decisión la tensión en la comunión eclesial entre los Obispos del Paraguay y mi persona y Diócesis: «no estamos en comunión», habría declarado el Nuncio en su conferencia.

Por mi parte, creo haber demostrado que los ataques y maniobras destituyentes de la que he sido objeto se iniciaron ya desde mi nombramiento como Obispo, antes incluso de que pudiera poner un pie en la Diócesis –hay correspondencia de la época entre los Obispos del Paraguay con el Dicasterio que Su Eminencia preside como prueba fehaciente de ello. Mi caso no ha sido el único en el que una Conferencia Episcopal se ha opuesto sistemáticamente a un nombramiento hecho por el Papa contra su parecer. Yo tuve la gracia de que, en mi caso, los Papas san Juan Pablo II y Benedicto XVI me apoyaran para seguir adelante. Entiendo ahora que el Papa Francisco haya decidido retirarme ese apoyo.

Sólo quiero destacar que no recibí en ningún momento un informe escrito sobre la Visita Apostólica y, por consiguiente, tampoco he podido responder debidamente a él. A pesar de tanto discurso sobre diálogo, misericordia, apertura, descentralización y respeto por la autoridad de las Iglesias locales, tampoco he tenido oportunidad de hablar con el Papa Francisco, ni siquiera para aclararle alguna duda o preocupación. Consecuentemente, no pude recibir ninguna corrección paternal –o fraternal, como se prefiera– de su parte. Sin ánimo de quejas inútiles, tal proceder sin formalidades, de manera indefinida y súbita, no parece muy justa, ni da lugar a una legítima defensa, ni a la corrección adecuada de posibles errores. Sólo he recibido presiones orales para renunciar.

Que mis opositores y la prensa local hayan recientemente estado informando en los medios, no de lo que había pasado, sino de lo que iba a suceder, incluso en los más mínimos detalles, es sin duda otro indicador de que algunas altas autoridades en el Vaticano, el Nuncio Apostólico y algunos Obispos del país estaban maniobrando de forma orquestada y dando filtraciones irresponsables para «orientar» el curso de acción y la opinión pública.

Como hijo obediente de la Iglesia, acepto, sin embargo, esta decisión por más que la considero infundada y arbitraria y de la que el Papa tendrá que dar cuentas a Dios, ya que no a mí. Más allá de los muchos errores humanos que haya cometido, y por los cuales desde ya pido perdón a Dios y a quienes hayan sufrido por ello, afirmo una vez más ante quien quiera escucharlo que la substancia del caso ha sido una oposición y persecución ideológica.

La verdadera unidad eclesial es la que se edifica a partir de la Eucaristía y el respeto, observancia y obediencia a la fe de la Iglesia enseñada normativamente por el Magisterio, articulada en la disciplina eclesial y vivida en la liturgia. Ahora, empero, se busca imponer una unidad basada, no sobre la ley divina, sino sobre acuerdos humanos y el mantenimiento del statu quo. En el Paraguay, concretamente, sobre la deficiente formación de un único Seminario Nacional –deficiencias señaladas no por mí, sino autoritativamente por la Congregación para la Educación Católica en carta a los Obispos de 2008. En contraposición, y sin criticar lo que hacían otros Obispos, aunque hay materia de sobra, yo me aboqué a establecer un Seminario diocesano según las normas de la Iglesia. Lo hice, además, no sólo porque tengo el deber y el derecho, reconocido por las leyes generales de la Iglesia, sino con la aprobación específica de la Santa Sede, inequívocamente ratificada durante la última visita ad limina de 2008.

Nuestro Seminario diocesano ha dado excelentes frutos reconocidos por recientes cartas laudatorias de la Santa Sede en al menos tres oportunidades durante el pontificado anterior, por los Obispos que nos han visitado y, últimamente, por los Visitadores Apostólicos. Toda sugerencia hecha por la Santa Sede en relación a mejoras sobre el modo de llevar adelante el Seminario, se han cumplido fielmente.

El otro criterio de unidad eclesiástica es la convivencia acrítica entre nosotros basada en la uniformidad de acción y pensamiento, lo que excluye el disentimiento por defensa de la verdad y la legítima variedad de dones y carismas. A esta uniformidad ideológica se la impone con el eufemismo de «colegialidad».

El que sufre las últimas consecuencias de lo que describo es el pueblo fiel, ya que las Iglesias particulares se mantienen en estado de letargo, con gran éxodo a otras denominaciones, casi sin vocaciones sacerdotales o religiosas, y con pocas esperanzas de un dinamismo auténtico y un crecimiento perdurable.

El verdadero problema de la Iglesia en el Paraguay es la crisis de fe y de vida moral que una mala formación del clero ha ido perpetuando, junto con la negligencia de los Pastores. Lugo no es sino un signo de los tiempos de esta problemática reducción de la vida de la fe a las ideologías de moda y al relajamiento cómplice de la vida y disciplina del clero. Como ya he dicho, no me ha sido dado conocer el informe del Cardenal Santos y Abril sobre la Visita Apostólica. Pero si fuera su opinión que el problema de la Iglesia en el Paraguay es un problema de sacristía que se resuelve cambiando al sacristán, estaría profunda y trágimente equivocado.

La oposicion a toda renovación y cambio en la Iglesia en el Paraguay no sólo ha contado con Obispos, sino también con el apoyo de grupos políticos y asociaciones anti-católicas, además del apoyo de algunos religiosos de la Conferencia de Religiosos del Paraguay –los que conocen la crisis de la vida religiosa a nivel mundial no se sorprenderán de esto último. El vocero pagado y reiteradamente mentiroso para tales maniobras ha sido siempre un tal Javier Miranda. Todo esto se hizo con la pretensión de mostrar «divisón» dentro de la misma Iglesia diocesana. Aunque la verdad demostrada y probada es la amplia aceptación entre el laicado de la labor que veníamos haciendo.

Del mismo modo que, antes de aceptar mi nombramiento como Obispo, me creí en la obligación de expresar vivamente mi sentimiento de incapacidad ante tamaña responsabilidad, después de haber aceptado dicha carga, con todo el peso de la autoridad divina y de los derechos y deberes que me asisten, he mantenido la gravísima responsabilidad moral de obedecer a Dios antes que a los hombres. Por eso me he negado a renunciar por propia iniciativa, queriendo así dar testimonio hasta el final de la verdad y la libertad espiritual que un Pastor debe tener. Tarea que espero continuar ahora desde mi nueva situación de servicio en la Iglesia.

La Diócesis de Ciudad del Este es un caso a considerar que ha crecido y multiplicado sus frutos en todos los aspectos de la vida eclesial, para felicidad del pueblo fiel y devoto que busca las fuentes de la fe y de la vida espiritual, y no ideologías politizadas y diluídas creencias que se acomodan a las opiniones reinantes. Ese pueblo expresó abierta y públicamente su apoyo a la labor apostólica que hemos venido haciendo. El pueblo y yo hemos sido desoídos.

Suyo afectísimo en Cristo,

+ Rogelio Livieres

Ex obispo de Ciudad del Este (Paraguay)

Ex obispo de Ciudad del Este (Paraguay)

La comunión se encuentra en la Eucaristía y no en consensos ideológicos

Nosotros, Obispos y Sacerdotes, no solo somos testigos de profundos cambios, sino actores comprometidos en esos procesos de transformación que afectan a diferentes ambientes de nuestra Iglesia. Y, como sucedió muchas veces a través de tantas épocas y lugares, también la crisis actual de la Iglesia radica principalmente en la herida Eucarística, en la irreverencia y falta de cuidado en el trato con Jesús Eucaristía.

En el mundo se sufre una profunda desacralización. En el Paraguay esto tiene forma de Teología de la Liberación, pero sus devastadoras ideas tuvieron origen en aceptaciones anteriores. Ideas y percepciones que lograron alterar el paradigma original de la relación del hombre con Dios, que era de filial correspondencia. Pretendida sustitución de lo sobrenatural por lo natural, de la Verdad que nos hace libres por una falsa liberación socioeconómica, como si esta pudiera hacerse efectiva sin sacudir previamente la esclavitud del pecado. Una hecatombe que desnudó los altares de Europa, desplazando a Dios y erigiendo al hombre como falso creador de un mundo cada vez más enfrentado a las cosas sagradas.

Ahora, después de años de constantes insinuaciones, la crisis (los problemas) en la Iglesia se hacen más visibles. Una crisis (problemas) que no podrán resolverse a través de un consenso generalizado sobre un cúmulo de ideas, nacidas justamente en un ámbito de creciente pérdida de respeto a lo más sagrado, a la Eucaristía. Por eso es necesario volver a uno de los conceptos fundamentales de este Sacramento, definido por el Concilio Vaticano II como “…signo de unidad…” (SC47).

El Catecismo nos recuerda que la “comunión de vida divina y la unidad del Pueblo de Dios, sobre los que la propia Iglesia subsiste, se significan adecuadamente y se realizan de manera admirable en la Eucaristía” (1325). La comunión se encuentra en este Sacramento y no en frágiles acuerdos sobre ideas.

La comunión en la Iglesia debe ser buscada y hallada en este excelso “signo de unidad”, en la Eucaristía. Sin embargo, hemos recorrido el camino inverso, cometiendo graves agravios, “heridas eucarísticas”.

Dejemos de maltratar a Dios en nuestra propia Iglesia. Tenemos que advertir sobre las graves consecuencias de recibir la Eucaristía en situaciones de inmoralidad o en la mano, propiciando el robo del Santo de los Santos. Si seguimos así, haremos perder la fe católica en la presencia real de Jesús en la Eucaristía.

Muchos en la Iglesia son indiferentes en su trato hacia Jesús Eucaristía. No podemos tomar por buenos abusos que en sí son destructivos. No debemos continuar en silencio: elevemos nuestras voces y defendamos lo más divino y concreto en esta tierra.

No olvidemos las advertencias de Dios por medio de su Profeta a los que tenemos responsabilidad sobre el pueblo: “A ti, hombre, yo te he puesto como centinela del pueblo de Israel. Pues bien, si tú no hablas con él para advertirle que cambie de vida, y él no lo hace, ese malvado morirá por su pecado, pero yo te pediré a ti cuentas de su muerte. En cambio, si tú adviertes al malvado que cambie de vida, y él no lo hace, él morirá por su pecado, pero tú salvarás tu vida”, (Ez. 33: 7-9).

+ Rogelio Livieres

http://diocesiscde.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3967:la-comunion-se-encuentra-en-la-eucaristia-y-no-en-consensos-ideologicos&catid=237:blog-del-obispo

S.E.R. Mons Rogelio Livieres Plano

Nació el 30 de agosto de 1945, realizó sus estudios de Bachiller en el Colegio San José de Asunción. Se recibió como Abogado, Notario y Escribano Público en la Universidad Católica “Nuestra Señora de la Asunción”.

Es Doctor en Derecho Canónico por la Universidad de Navarra (España) y especialista en Derecho Administrativo por la Escuela Nacional de Administración Pública de Madrid (España).

Fue ordenado Sacerdote el 15 de Agosto de 1978, perteneciendo al clero de la Prelatura de la Santa Cruz y Opus Dei.

Ha desarrollado su servicio sacerdotal en la actividad pastoral directa como Vicario de la Prelatura de la Santa Cruz y Opus Dei en Buenos Aires, Capellán de la Universidad Austral en Buenos Aires y en el Centro Universitario CUDES. Ya en la ciudad de Asunción fue Capellán de la Escuela de Formación para la asistencia de Empresas de Servicios (EFAES) y en el Centro Universitario Ycuá.

Además ha llevado adelante una labor académica como Profesor de Filosofía del Derecho en la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Nacional del Este (UNE) y en la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Católica sede en Alto Paraná. Así como Profesor de Introducción al Derecho en la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas de la Universidad Católica de Asunción, Profesor de Derecho Administrativo en la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Navarra (España), Profesor de Derecho Canónico en el Seminario Internacional de Prelatura de la Santa Cruz y Opus Dei en Roma y Profesor de Teología en la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Austral de Buenos Aires.

Fue nombrado como obispo de Ciudad del Este por el Papa Juan Pablo II, el 12 de julio del 2004 y tomó posesión del cargo el 3 de octubre del mismo año.

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Fatima Rosary Prayer in Latin

salva nos ab igne inferiori.

Perduc in caelum omnes animas,

praesertim eas, quae misericordiae tuae maxime indigent.

Obituary of the Holy Roman Empire

"On December 30, 1797, at three in the afternoon, the Holy Roman Empire, supported by the Sacraments, passed away peacefully at Regensburg at the age of 955, in consequence of senile debility and an apoplectic stroke. The deceased was born at Verdun in the year 842, and educated at the Court of Charles the Simple and his successors. The young prince was taught piety by the Popes, who canonised him in his lifetime. But his tendency to a sedentary life, combined with zeal for religion, undermined his health. His head became visibly weaker, till at last he went mad in the Crusades. Frequent bleedings and careful diet restored him; but, reduced to a shadow, the invalid tottered through the centuries till violent hemorrhage occurred in the Thirty Years' War. Hardly had he recovered when the French arrived, and a stroke put an end to his sufferings. He kept himself unstained by the Aufklärung, and bequethed the left bank of the Rhine to the French Republic."

--Görres (Cf. Germany and the French Revolution, Gooch p. 516)

N.B. In the thought of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI the best legacy of the Holy Roman Empire is coupled with the best Enlightenment ideals to find perfect harmony and fruition as the foundation for a rebirth of Western Civilization. Freedom, Fraternity and Equality are anchored in Paternity and Faith. Reason gets religion and finally understands itself.

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

ComparingThree Popes

Pope Saint John Paul II told us what to do.

Benedict XVI told us why we should do it.

Francis is telling us – “Do it.”

Archbishop Blase Cupich, newly named Archbishop of Chicago's, closing words during the above address.

N.B. On the Liturgical and Ecclesial chaos which continues in Chicago, check out this "Mass" homily! Wow!

Benedict XVI told us why we should do it.

Francis is telling us – “Do it.”

Archbishop Blase Cupich, newly named Archbishop of Chicago's, closing words during the above address.

N.B. On the Liturgical and Ecclesial chaos which continues in Chicago, check out this "Mass" homily! Wow!

Monday, September 22, 2014

The History of the Popes: the Center of Modern Science

|

| Father Johannes Jannsen |

SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 Crisis mAGAZINE

Ludwig von Pastor & the History of the Popes

THOMAS J. MAURO

Joseph de Maistre once wrote that “The scepter of science belongs to Europe only because she is Christian. She has reached this high degree of civilization and knowledge because … the universities were at first schools of theology, and because all the sciences, grafted upon this divine subject, have shown forth the divine sap by immense vegetation.” We have in recent years become increasingly familiar with the notion that the birth and flourishing of science in the Christian West, rather than in some other historical civilization or corner of the world, most probably had something to do with the Logocentric nature of Christianity. Non-Christians themselves are increasingly inclined to admit this. But while Pierre Duhem illustrated the idea of the theological matrix of modern science by tracing the background of the so-called Scientific Revolution, Maistre was thinking along broader lines in his conception of science.

We do not usually consider historical studies when we think about science and its growth, although we do sometimes consider history a social science. Probably closer to Maistre’s general view, however, was Leibniz, who considered historical consciousness and the development of historical criticism as one of the chief glories of Christendom. “I believe,” he wrote, “that if this art [of historical criticism] has reappeared with brilliant effect, and has been so carefully cultivated in the last two centuries … it is an act of Divine Providence, which had chiefly in view to spread more light on the truth of the Christian religion…. I believe that the great obstacle to Christianity in the East is that these nations are completely ignorant of universal history, and do not therefore feel the force of those demonstrations by which the truth of our religion is established.”

| Ludwig Pastor |

Leibniz explicitly linked the development of historical studies with the phenomenon of theological debate. “The disputes on religion,” he writes, “encouraged and excited this sort of study, for there is no evil that does not give birth to some good.” The notion that theological conflict had at least one beneficial effect in Europe was expressed more recently by Momigliano, who concluded: “A new chapter of historiography begins with Eusebius [in the fourth century] not only because he invented ecclesiastical history, but because he wrote it with a documentation which is utterly different from that of the pagan historians … we have all underestimated the impact of ecclesiastical history on the development of historical method.” A secular Jew, Momigliano cannot be suspected of special pleading here. Of course the historical claims of the Gospels (cf. 1 Cor 15:14) and the authenticity (or not) of apostolic traditions had from the beginning been points of contention; perhaps it is not implausible to think that traditional Christian notions of orthodoxy and heresy could not fail to stimulate historical consciousness and investigation.

After being eclipsed by rhetoric and speculation in the eighteenth century, historical studies made a strong comeback in the nineteenth century, a revival often associated with Leopold von Ranke, widely regarded as the most influential historian of the nineteenth century. Although Ranke himself was a moderate in that age of nationalism, he nevertheless did his part to buttress a Prussian version of history that was marked by a strongly anti-Catholic prejudice. In the typical Prussian view, Luther was seen as not only a great religious reformer, but as a national hero, a “Founding Father,” as it were, who had literally brought the German people out of the darkness of the Middle Ages.

Even among German Protestants there were critics of this view. One of the sharpest was the Frankfurt medievalist Johann Friedrick Böhmer (1795-1863), whose considered view was that the so-called Reformation had been an epic disaster for Germany and for Europe and that Prussia’s recent rise constituted one of the greatest contemporary threats to European civilization. Böhmer himself became the mentor of Johannes Janssen (1829-1891) who, largely inspired by him, would come out with a multi-volumeHistory of the German People that became one of the best-selling and most widely discussed historical works in Bismarck’s Germany.

Janssen expanded the scope of Ranke’s highly empirical method to include cultural history, and in so doing turned the “Prussian view” of history on its head. After establishing his reputation with earlier works in which he skillfully exploited the riches of German archives, especially those of Frankfurt, the first volume of his magnum opuswas dedicated to showing how highly developed and flourishing German culture had become in the fifteenth century, that is, prior to the Reformation. Subsequent volumes documented the post-Reformation decline into darkness and chaos, ultimately culminating in the devastation of the Thirty Years’ War. Coming as it did from the pen of a staunchly Catholic author in the midst of the Kulturkampf, this view could not fail to attract attention, much of it hostile. But it was so solidly buttressed, employing such a vast range of primary documents that its author had spent a lifetime collecting, that critics were hard pressed to dismiss it. A wealthy German-American offered a prize of $5,000 for the best refutation of Janssen’s work. The prize was never awarded. As the great Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt (who had been offered and declined Ranke’s chair in Berlin) quipped to his students in Basel: “Believe me, gentlemen, whoever wants to confute Janssen will have to get up pretty early in the morning.” (Ja ja, meine Herren, wer Janssen widerlegen will, der muß früh aufstehen.) As subsequent volumes appeared Janssen would even be hailed by Georg Waitz, the most prominent disciple of Leopold von Ranke, as “the greatest living German historian,” an assessment he gave while Ranke himself was still alive. Burckhardt himself would later say that Janssen “has finally told us the truth about the so-called Reformation. Up until now we’ve had only the pious stories of Protestant pastors.”

Janssen’s most distinguished student was Ludwig von Pastor (1854-1928), remembered today as one of the greatest ecclesiastical historians of all times. Pastor had been born into a well-to-do family in Aachen, Germany. His sincerely Protestant father and Catholic mother had agreed that their sons would be raised as Protestants and daughters as Catholics. The future historian of the papacy was thus duly baptized as a Protestant and, as the eldest son, was being groomed to take over the sizable family business. His father died, however, while Ludwig was still young, and partially under the influence of his mother’s friends and acquaintances in Frankfurt, where the family had relocated, but especially because of his history teacher, Johannes Janssen, his life would take a different path.

Janssen himself had declined more prestigious posts (and would eventually even decline the cardinal’s hat offered him by Leo XIII) in order to stay at the Frankfurt gymnasium, where he was charged with teaching the Catholic students. He immediately recognized the young Pastor’s gifts and aptitudes, and became a close friend of the family. As Pastor later recounted: “Janssen visited us every week at our house. Whenever possible, I accompanied him on his walks. When Janssen lived in Niederrad in 1870, I visited him every Sunday after Mass and stayed with him the whole day in the woods. These were precious hours. First, the events of the day were discussed. Then we read classics together. Janssen introduced me to all his work. Through him I got to know the historical journals. He gave me in 1871 a copy of Burckhardt’s Culture of the Renaissance and in 1873 Ranke’s Popes, and thus the impetus for my life’s work.”

This last sentence is especially important in showing that Pastor’s entire work can be seen in a way as a reply to Burckhardt and Ranke. And in fact, Ranke’s The Roman Popes in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1834-36) would serve as a stimulus to the 19-year-old Pastor in much the same way as Ranke’s History of the Reformation in Germany (1845-47) had been an impetus to his mentor, Janssen.

Pastor was twelve years old as the Prussians defeated the majority of the German states and Austria in the German Civil War of 1866, and his family was compelled to flee temporarily to Cologne. Triumphant Prussia’s subsequent introduction of theKulturkampf would only intensify his dedication to the vision of Catholic history to which Janssen had introduced him.

Graduating from the gymnasium in 1875, Pastor would go first, on Janssen’s advice, to the University of Louvain, and then would continue his studies at Bonn, Berlin (where he was introduced to Leopold von Ranke himself), Vienna, and finally Graz, where he obtained his doctorate in 1878 with a dissertation on Church reunion attempts during the reign of Charles V. It was during this doctoral work that he became convinced that certain important problems could only be solved by an examination of original documents which he surmised were in the papal archives, at this time closed to researchers. With a zeal that was characteristic of his entire career, he wrote to various churchmen, penned two petitions, and finally sought an audience with the pope himself. Eventually he became more responsible than any other single scholar for persuading Leo XIII to open the papal archives to all, regardless of religious affiliation, in 1883. In an audience granted to a select group of historians the next year, the pope indicated both the opportunity and the responsibility that now faced Pastor, telling him: “Owing to this decree you have good advantages over Ranke…. Naturally it will also spread your fame as an historian. However, our highest aim in this grant was the honor of God and the glory of his Church.” Then addressing all present he continued: “True history must be written from the original sources. Therefore we opened the Vatican Archives to the historians for investigation. We have nothing to fear from the publication of documents. (Non abbiamo paura della pubblicità dei documenti.) Every pope, more or less, worked, some even under the greatest difficulties, for the propagation of the kingdom of God on earth and among all nations, for the Church is the mother of all…. Work courageously and perseveringly, not only for earthly reward and worldly honor, but for the glory of Him that He may crown these labors with heavenly bliss.”

Despite his solid training and the best references, it was made clear to Pastor that someone with his views would have no chance of obtaining a university post in his homeland while the Kulturkampf still raged. “Here you’d have better chances of becoming a bishop than a university professor,” a German friend told him. It was only with difficulty that he managed to find a position in 1880 at the small university of Innsbruck, Austria, where he would spend the next twenty years. Even here, opponents would strain every nerve to prevent his advancement to a professorship. Only with the fame following the publication of the first volume of his History of the Popes in 1886 would his academic career be secure. With a succession of volumes of equally high quality it would not be long before he would receive numerous honorary degrees, and finally be raised to the rank of hereditary nobility by the emperor Franz Josef. In 1900 he was appointed the Director of the Austrian Historical Institute in Rome. This gave him an uninterrupted fourteen years to explore Roman archives and to enrich his history, which he continued to revise until his death. Although forced to leave the Eternal City during the Great War, he returned again in 1920 as the Austrian Ambassador to the Holy See.

Pastor’s first volume was dedicated to Leo XIII and, after an overview of the period of the Avignon papacy, the Great Schism, and the reunification at the Council of Constance, it began in earnest with the pontificate of Martin V in 1417. In Pastor’s lifetime 13 thick volumes (29 in the English version) would be delivered to the printer, covering the papacy in the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Catholic revival up through the pontificate of Urban VIII and the middle of the Thirty Years’ War. The manuscript bringing the history down to 1799 was essentially finished at his death and was brought out posthumously. In all, 16 volumes would appear (40 in the English version) covering a period of 400 years. Pastor himself was convinced that he was only able to reach his goal, despite failing eyesight, because of a blessing received by Pius X, to whom he dedicated volume two.

Astonishingly, he also managed to write other works. The most ambitious of these was his continuation of Janssen’s History of the German People, a work that had “opened up a new world” for the young Pastor himself. At Janssen’s death in 1891 only six volumes had been published. Janssen had appointed Pastor his literary executor, and the latter not only finished the last two volumes, but he revised and expanded the previous volumes so extensively that it is now conventionally cited as “Janssen-Pastor.” In addition to editing a series of monographs dedicated to elucidating themes touched upon in Janssen’s volumes, he also found time to write biographies, editions of letters and documents, and many other special studies.

The work for which he is and will remain best known, however, is the massive History of the Popes. In directing an almost superhuman energy steadily over a period of fifty years, during which he pushed himself to nervous exhaustion at least four times, he succeeded in forging a monumental and permanent achievement, solidly built on the best methods of German historical scholarship when that scholarship had reached its highest level of perfection.

Pastor’s first volume appeared in the same year that Ranke died. It could not fail to be noticed that it was, in a certain sense, a reply to Ranke’s classic work using Rankean methods. Yet it was not merely a political history. It was rather a Kulturgeschichte as seen from the central vantage point of Rome, and in that sense too it was clearly connected with Janssen’s project. Pastor’s volumes found an almost universally sympathetic reception in most of the German world. “Never before,” reported theIllustrierte Rundschau, “has material of such abundance been brought together and made use of in such a way that the unbiased Protestant can fully rely on its deductions.” Jacob Burckhardt himself wrote appreciatively to Pastor for correcting his (Burckhardt’s) unbalanced picture of Renaissance religiosity in the Culture of the Renaissance, and a mutually respectful friendship ensued. A passage from the Jesuit journal Stimmen aus Maria Laach can be taken as representative of Catholic reaction:

Neither Macaulay nor Ranke gave a satisfactory answer as to why so many millions left the Church during the sixteenth century. It is indeed true, Ranke did not, like the first Reformers in their first anger, look upon the papacy as an institution of the Antichrist. He valued it only as a great political power that contributed much to the progress of the world. Still it is for him merely a government founded on the quicksands of deception. In a similar manner Macaulay calls it a great civilizing agent. Pastor proves or corrects these statements and adds another most essential point: the spirituality of the papacy. Thus we get a more complete picture of that entire period.

Although initially slow to find favor in the English-speaking world, by the time his last volumes appeared even Pastor’s critics in the American Historical Review would come to concede: “His volumes are of inestimable worth to men of every faith.” Likewise the British historian G. P. Gooch, who in penning his classic History and Historians in the Nineteenth Century (1913) had declined to list Pastor among historians of the first rank, when revising his book four decades later would change his tone significantly. Then he would conclude with a judgment that we are certainly justified in sharing: “Pastor’s gigantic History of the Popes since the end of the Middle Ages, based on the Vatican and other Italian archives, the first volume of which had appeared in 1886, reached its thirteenth volume in 1928, the year of his death…. No work of our time—perhaps of any time—in the domain of Church History has made such an opulent and enduring contribution to knowledge.”

By Thomas J. Mauro

Dr. Thomas J. Mauro completed his undergraduate studies at Oxford and Columbia, and pursued graduate studies at the University of Chicago and Princeton University. He has advanced degrees in Classics and in European History. He writes from Lugano, Switzerland.

Cf. Science and Creation, Jaki. Jaki shows that throughout the history of science it was repeatedly faith which served as the basis for the rational stability necessary for science.

Cf. Science and Creation, Jaki. Jaki shows that throughout the history of science it was repeatedly faith which served as the basis for the rational stability necessary for science.

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Church, Scripture and Liturgy

You cannot understand the Old Testament without the Temple.

You cannot understand the New Testament without the Mass!

The Bible is above all a Liturgical book! Catholic cult is the key to understanding the Bible. You cannot be expert in Sacred Scripture unless you go to Mass and experience the living Word.

Go to Mass. Don't be afraid. No one will bother you. And you will surely encounter Christ in the most direct way possible on earth.

A Jew who has never gone to Mass will never properly understand Judaism.

A Protestant who has never gone to Mass will never fully understand what it means to be Christian.

A Catholic who does not love the Mass is the greatest of fools and a hypocrite!

Go to Mass, especially the Traditional Latin Mass! And do all in your power to understand and participate interiorly. And go again and again and again. You will get it and will go infinitely deep in the mystery of the living God.

The Mass works! It is opus Dei: God's work.

The Catholic Liturgy is Divine historical action, God's direct and immediate intervention in the world! Scripture is a record of a part of that Divine action, which continues even today, in the liturgical proclamation and worship with the sacred texts. The texts are alive in the Liturgy: the Holy Spirit is doing the action through the ministry of the Church.

Faith comes through hearing, principally at Mass!

Romans (Douay-Rheims Bible)

10:1 BRETHREN, the will of my heart, indeed, and my prayer to God, is for them unto salvation.

10:2 For I bear them witness, that they have a zeal of God, but not according to knowledge.

10:3 For they, not knowing the justice of God, and seeking to establish their own, have not submitted themselves to the justice of God.

10:4 For the end of the law is Christ, unto justice to every one that believeth.

10:5 For Moses wrote, that the justice which is of the law, the man that shall do it, shall live by it.

10:6 But the justice which is of faith, speaketh thus: Say not in thy heart, Who shall ascend into heaven? that is, to bring Christ down;

10:7 Or who shall descend into the deep? that is, to bring up Christ again from the dead.

10:8 But what saith the scripture? The word is nigh thee, even in thy mouth, and in thy heart. This is the word of faith, which we preach.

10:9 For if thou confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and believe in thy heart that God hath raised him up from the dead, thou shalt be saved.

10:10 For, with the heart, we believe unto justice; but, with the mouth, confession is made unto salvation.

10:11 For the scripture saith: Whosoever believeth in him, shall not be confounded.

10:12 For there is no distinction of the Jew and the Greek: for the same is Lord over all, rich unto all that call upon him.

10:13 For whosoever shall call upon the name of the Lord, shall be saved.

10:14 How then shall they call on him, in whom they have not believed? Or how shall they believe him, of whom they have not heard? And how shall they hear, without a preacher?

10:15 And how shall they preach unless they be sent, as it is written: How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, of them that bring glad tidings of good things!

10:16 But all do not obey the gospel. For Isaias saith: Lord, who hath believed our report?

10:17 Faith then cometh by hearing; and hearing by the word of Christ.

10:18 But I say: Have they not heard? Yes, verily, their sound hath gone forth into all the earth, and their words unto the ends of the whole world.

10:19 But I say: Hath not Israel known? First, Moses saith: I will provoke you to jealousy by that which is not a nation; by a foolish nation I will anger you.

10:20 But Isaias is bold, and saith: I was found by them that did not seek me: I appeared openly to them that asked not after me.

10:21 But to Israel he saith: All the day long have I spread my hands to a people that believeth not, and contradicteth me.

11:1 I SAY then: Hath God cast away his people? God forbid. For I also am an Israelite of the seed of Abraham, of the tribe of Benjamin.

11:2 God hath not cast away his people, which he foreknew. Know you not what the scripture saith of Elias; how he calleth on God against Israel?

11:3 Lord, they have slain thy prophets, they have dug down thy altars; and I am left alone, and they seek my life.

11:4 But what saith the divine answer to him? I have left me seven thousand men, that have not bowed their knees to Baal.

11:5 Even so then at this present time also, there is a remnant saved according to the election of grace.

Cf. The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI, Emery de Gaál, p. 119

"As a student, Ratzinger learned from Romano Guardini that liturgy is the proper context to understand the Bible: it is the product of the Church celebrating the Eucharist and proclaiming the gospel. Church, scripture, and liturgy form one hermeneutic unit. A person cannot understand one without the two other elements. Famously, Kant had argued that the voice of being itself cannot be heard by human beings shackled to contingent, phenomenal reality. Only the postulates of practical reason access God. In contrast, John the Evangelist holds that the Spirit-inspired memory of the 'we' of the Church brings about a remembering of the reality underlying scripture. Divine initiative is not constrained by a Kantian perspective. Only with the Easter Kerygma (preaching) does the integrity of scripture become apparent. All else evaporates into private musings or even ideologies. Good exegesis 'is rooted in the living reality...of the Church of all ages.'"

Friday, September 19, 2014

A Thought for Middle Age

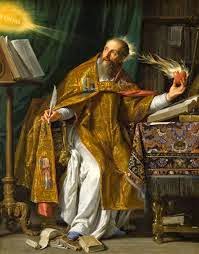

The Light of Truth and the Light of Love: Saint Augustine's Three Conversions in Lumen Fidei

Saint Augustine Finds the Truth in Transcendence, Immanence and in the Ongoing Relationship with God in Christ.

33. In the life of Saint Augustine we find a significant example of this process whereby reason, with its desire for truth and clarity, was integrated into the horizon of faith and thus gained new understanding. Augustine accepted the Greek philosophy of light, with its insistence on the importance of sight. His encounter with Neoplatonism introduced him to the paradigm of the light which, descending from on high to illumine all reality, is a symbol of God. Augustine thus came to appreciate God’s transcendence and discovered that all things have a certain transparency, that they can reflect God’s goodness. This realization liberated him from his earlier Manichaeism, which had led him to think that good and evil were in constant conflict, confused and intertwined. The realization that God is light provided Augustine with a new direction in life and enabled him to acknowledge his sinfulness and to turn towards the good.

All the same, the decisive moment in Augustine’s journey of faith, as he tells us in the Confessions, was not in the vision of a God above and beyond this world, but in an experience of hearing. In the garden, he heard a voice telling him: "Take and read". He then took up the book containing the epistles of Saint Paul and started to read the thirteenth chapter of the Letter to the Romans.[28] In this way, the personal God of the Bible appeared to him: a God who is able to speak to us, to come down to dwell in our midst and to accompany our journey through history, making himself known in the time of hearing and response.

Yet this encounter with the God who speaks did not lead Augustine to reject light and seeing. He integrated the two perspectives of hearing and seeing, constantly guided by the revelation of God’s love in Jesus. Thus Augustine developed a philosophy of light capable of embracing both the reciprocity proper to the word and the freedom born of looking to the light. Just as the word calls for a free response, so the light finds a response in the image which reflects it. Augustine can therefore associate hearing and seeing, and speak of "the word which shines forth within".[29] The light becomes, so to speak, the light of a word, because it is the light of a personal countenance, a light which, even as it enlightens us, calls us and seeks to be reflected on our faces and to shine from within us. Yet our longing for the vision of the whole, and not merely of fragments of history, remains and will be fulfilled in the end, when, as Augustine says, we will see and we will love.[30] Not because we will be able to possess all the light, which will always be inexhaustible, but because we will enter wholly into that light.

34. The light of love proper to faith can illumine the questions of our own time about truth. Truth nowadays is often reduced to the subjective authenticity of the individual, valid only for the life of the individual. A common truth intimidates us, for we identify it with the intransigent demands of totalitarian systems. But if truth is a truth of love, if it is a truth disclosed in personal encounter with the Other and with others, then it can be set free from its enclosure in individuals and become part of the common good. As a truth of love, it is not one that can be imposed by force; it is not a truth that stifles the individual. Since it is born of love, it can penetrate to the heart, to the personal core of each man and woman. Clearly, then, faith is not intransigent, but grows in respectful coexistence with others. One who believes may not be presumptuous; on the contrary, truth leads to humility, since believers know that, rather than ourselves possessing truth, it is truth which embraces and possesses us. Far from making us inflexible, the security of faith sets us on a journey; it enables witness and dialogue with all.

Nor is the light of faith, joined to the truth of love, extraneous to the material world, for love is always lived out in body and spirit; the light of faith is an incarnate light radiating from the luminous life of Jesus. It also illumines the material world, trusts its inherent order and knows that it calls us to an ever widening path of harmony and understanding. The gaze of science thus benefits from faith: faith encourages the scientist to remain constantly open to reality in all its inexhaustible richness. Faith awakens the critical sense by preventing research from being satisfied with its own formulae and helps it to realize that nature is always greater. By stimulating wonder before the profound mystery of creation, faith broadens the horizons of reason to shed greater light on the world which discloses itself to scientific investigation.

Pavia Homily on the Three Conversions of Saint Augustine

To Christ and Away From Sin

For Others

To the Ongoing Need for Mercy (never done with needing Jesus).

General Audience.

The third conversion

Approximately 20 years [after his ordination], Augustine wrote a book called the Retractations, in which he critically reviewed all the works he had thus far written, adding corrections wherever he had in the meantime learned something new.

With regard to the ideal of perfection in his homilies on the Sermon on the Mount, he noted: "In the meantime, I have understood that one alone is truly perfect and that the words of the Sermon on the Mount are totally fulfilled in one alone: Jesus Christ himself.

"The whole Church, on the other hand -- all of us, including the Apostles -- must pray every day: forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us" (cf. Retract. I 19, 1-3).

Augustine had learned a further degree of humility -- not only the humility of integrating his great thought into the humble faith of the Church, not only the humility of translating his great knowledge into the simplicity of announcement, but also the humility of recognizing that he himself and the entire pilgrim Church needed and continually need the merciful goodness of a God who forgives every day.

And we, he added, liken ourselves to Christ, the only Perfect One, to the greatest possible extent when we become, like him, people of mercy. Pavia Homily

To Christ and Away From Sin

For Others

To the Ongoing Need for Mercy (never done with needing Jesus).

General Audience.

The third conversion

Approximately 20 years [after his ordination], Augustine wrote a book called the Retractations, in which he critically reviewed all the works he had thus far written, adding corrections wherever he had in the meantime learned something new.

With regard to the ideal of perfection in his homilies on the Sermon on the Mount, he noted: "In the meantime, I have understood that one alone is truly perfect and that the words of the Sermon on the Mount are totally fulfilled in one alone: Jesus Christ himself.

"The whole Church, on the other hand -- all of us, including the Apostles -- must pray every day: forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us" (cf. Retract. I 19, 1-3).

Augustine had learned a further degree of humility -- not only the humility of integrating his great thought into the humble faith of the Church, not only the humility of translating his great knowledge into the simplicity of announcement, but also the humility of recognizing that he himself and the entire pilgrim Church needed and continually need the merciful goodness of a God who forgives every day.

And we, he added, liken ourselves to Christ, the only Perfect One, to the greatest possible extent when we become, like him, people of mercy. Pavia Homily

.jpg)