|

| This is the image from His Holiness Pope Francis' February 17th visit to the Mexican-American boarder Jesus, Mary and Joseph crossing (in place of Christ crucified) on the cross! "You did it to me." Matthew 25:45 |

Thursday, June 30, 2016

Jesus, Mary and Joseph on Rio Grande Cross

Straight Pride!

|

| #HeterosexualPrideDay |

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Communion with Christ includes Communion with the Pope

|

| Porta del Popolo flanked by Saints Peter and Paul The Patrons of Rome |

Recognition of the papacy does not belittle the role of Christ, the Head of the Church; it is rather a recognition of the triumphant power of his grace; it is a recognition of what he effects through human beings, of what only he can effect. It may be objected here that theoretically this is all fine and good, but how does it work on practice? How can we claim that our sole focus is Christ when the Pope is the visible focus of the Church's unity? The answer is perhaps nowhere so clearly evident as in the fundamental prayer of the Church, the Eucharist, in which the center of her life is not only expressed, but consummated day after day. Christ is profoundly and solely the center of the Eucharist. He prays for us, he puts his prayer on our lips, for only he can say "This is my Body...;this is my Blood". In this way he incorporates us into his life, into his act of eternal love. Following an ancient tradition, we, for our part, say at each celebration of the Eucharist: we celebrate it together with our Pope. Christ gives himself in the Eucharist and he is, in every place, the one Christ; therefore wherever the Eucharist is celebrated the whole mystery of the Church is present. Precisely because the whole, undivided, and indivisible Christ is present in the Eucharist, the Eucharist can be properly celebrated only when it is celebrated with the whole Church. We have Christ only when we have him with others. Because the Eucharist is solely about Christ, it is, for that reason, the sacrament of the Church. And, for the same reason, it can be celebrated only in the unity of the whole Church and with the fullness of her power. That is why the Pope has a place in the eucharistic prayer. Communion with him is communion with the whole; without it, there is no communion with Christ.

Joseph Ratzinger, Co-Workers of the Truth, San Francisco: Ignatius, 1992, entry for June 30, p. 209.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Know Thyself!

|

| The Prodigal Son: Pompeo Batoni |

We would not be able to know which art would make oneself better if we did not know what we ourselves are. But is it perchance easy to know oneself; and was it a good-for-nothing he who put that inscription on the temple of Delphi; or rather is it a matter of something difficult and not within the reach of all? Whether it be easy or not, for us the question is put this way: knowing ourselves we will be able to know how we should take care of ourselves; while, if we ignore the former we shall not at all know the latter.

Plato, Alcibiades 1, 128 E - 129 A

Apostle's Creed, Literally

Each Apostle contributes on of the twelve articles.

This theory is documented as early as the 6th century.

Cf. Raztinger, Revelación e Historia de la Salvación (1955), BAC: Madrid, 2013, 159.

I first came across this account on the walls of the sacristy of the Basilica of Saint James (Santiago de Compostela).

This theory is documented as early as the 6th century.

Cf. Raztinger, Revelación e Historia de la Salvación (1955), BAC: Madrid, 2013, 159.

I first came across this account on the walls of the sacristy of the Basilica of Saint James (Santiago de Compostela).

Sunday, June 26, 2016

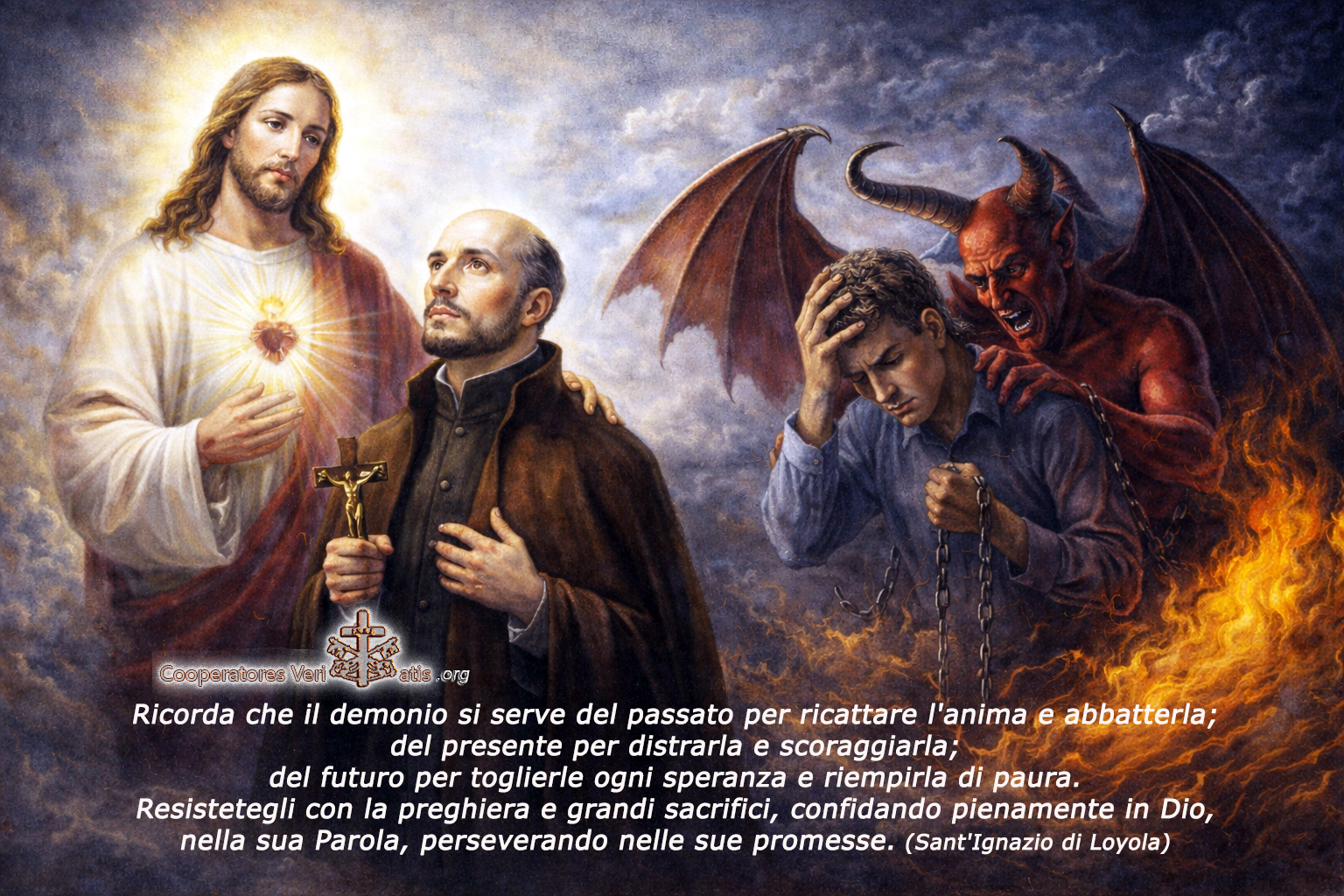

This sign on the wall of the refectory of the convent of the Santuario y Museo Santa Maria Bernarda, Cartagena, Colombia, sums up the remarkable Catholic disposition of the people of Cartagena who all work to get by but with large hearts of Christian love. The street vendors and the taxi drivers all have faith in Jesus Christ and radiate his love and generosity.

They give more than they take! That's Catholic!

The walled city of Cartagena is home to the Basilica of Saint Peter Claver, the Apostle of the Slaves.

I said Mass daily on the high altar (on his sarcophagus). The Jesuits there were most accommodating, and the elderly Father Trulio (translator of the cause of canonization) obtained a first class relic for me of the Saint!

They give more than they take! That's Catholic!

The walled city of Cartagena is home to the Basilica of Saint Peter Claver, the Apostle of the Slaves.

I said Mass daily on the high altar (on his sarcophagus). The Jesuits there were most accommodating, and the elderly Father Trulio (translator of the cause of canonization) obtained a first class relic for me of the Saint!

Plinthos reading the gospel at Mass on the tomb of "The Slave of the 'Ethiopians.'"

Friday, June 24, 2016

Eros for Truth: "Love Seeks Understanding"

"Faith can wish to understand because it is moved by love for the One upon whom it has bestowed its consent (Bonaventura, Sent., q 2 ad 6). Love seeks understanding. It wishes to know ever better the one whom it loves. It 'seeks his face', as Augustine never tires of repeating (See, for example, En in ps 104, 3 C Chr XL p. 1537). Love is the desire for intimate knowledge, so that the quest for intelligence can even be an inner requirement of love. Put another way, there is a coherence of love and truth which has important consequences for theology and philosophy. Christian faith can say of itself, I have found love. Yet love for Christ and of one's neighbor for Christ's sake can enjoy stability and consistency only if its deepest motivation is love for the truth. This adds a new aspect to the missionary element: real love of neighbor also desires to give him the deepest thing man needs, namely, knowledge of truth...[L]ove, the center of Christian reality on which 'depend the law and the prophets', is at the same time eros for truth, and only so does it remain sound as agape for God and man."

"Faith, Philosophy and Theology" in The Nature and Mission of Theology, Joseph Ratzinger, San Francisco: Ignatius, 1995, 27.

Thursday, June 23, 2016

"Alice in 'Amoris Laetitia' Land": An Detailied Expert Analysis of the Perplexities Therein

by Anna M. Silvas

In this talk I would like to outline some of the more pressing concerns I have with "Amoris Laetitia". These reflections are organised into three sections. Part one will outline general concerns; part two will focus on the now infamous chapter eight; and part three will suggest some of the implications of "Amoris Laetitia" for priests and catholicism.

I am aware that "Amoris Laetitia", as an apostolic exhortation, does not come under any rubric of infallibility. Still it is a document of the papal ordinary magisterium, and thus it makes the idea of critiquing it, especially doctrinally, mighty difficult. It seems to me unprecedented situation. I wish there were a great saint, like St Paul, or St Athanasius or St Bernard or St Catherine of Siena who could have the courage and the spiritual credentials, i.e. prophecy of the truest kind, to speak the truth to the successor of Peter and recall him to a better frame of mind. At this hour, hierarchical authority in the Church seems to have entered a strange paralysis. Perhaps this is the hour for prophets – but true prophets. Where are the saints, of "nooi" (intellects) long purified by contact with the living God in prayer and ascesis, gifted with the anointed word, capable of such a task? Where are these people?

General concerns

Graven upon tablets of stone by the finger of the living God (Ex 31:18, 32:1 5), the ten "words" proclaimed to mankind for all ages: "You shall not commit adultery" (Ex 20:14), and: "You shall not covet your neighbour’s wife" (Ex 20:17).

Our Lord himself declared: "Whoever divorces his wife and marries another, commits adultery against her (Mk 10:11).

And the apostle Paul repeated the language: "She will be called an adulteress if she lives with another man while her husband is alive" ( Rom 7:3 ).

Like a deafening absence, the term "adultery" is entirely absent from the lexicon of "Amoris Laetitia". Instead we have something called "'irregular' unions", or "irregular situations”, with the "irregular" in double quotation marks as if to distance the author even from this usage.

"If you love me", says our Lord, keep my commandments (Jn 14:15), and the Gospel and Letters of John repeats this admonition of our Lord in various ways. It means, not that our conduct is justified by our subjective feelings, but rather, our subjective disposition is verified in our conduct, i.e., in the obediential act. Alas, as we look into AL, we find that "commandments" too are entirely absent from its lexicon, as is also obedience. Instead we have something called "ideals", appearing repeatedly throughout the document.

Other key words I miss too from the language of this document: the fear of the Lord. You know, that awe of the sovereign reality of God that is the beginning of wisdom, one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit in confirmation. But indeed this holy fear has long vanished from a vast sweep of modern catholic discourse. It is a semitic idiom for "eulabeia" and "eusebia" in Greek, or in Latin, "pietas" and "religio", the core of a God-ward disposition, the very spirit of religion.

Another register of language is also missing in "Amoris Laetitia" is that of eternal salvation. There are no immortal souls in need of eternal salvation to be found in this document! True, w e do have "eternal life" and "eternity" nominated in nn. 166 and 168 as the seemingly inevitable "fulfillment" of a child’s destiny, but with no hint that any of the imperatives of grace and struggle, in short, of eternal salvation, are involved in getting t here.

It is as if one’s faith-filled intellectual culture is formed to certain echoes of words that one listens for, and their absence is dinning in my ears. Let us look then into what we have in the document itself.

Why the sheer wordiness of it, all 260 pages of it, more than three times the length of "Familiaris Consortio"? This is surely a great pastoral discourtesy. Yet Pope Francis wants "each part" to be "read patiently and carefully" (n. 7). Well, some of us have had to do so. And so much of it is of a tedious, light-weight character. In general I find Pope Francis’ discourse, not only here, but everywhere else, flat and one dimensional. "Shallow" might capture it, and "facile" too: no sense of depth upon depth lying beneath words holy and true, inviting us to launch into the deep.

One of the least pleasant features of "Amoris Laetitia" are Pope Francis’ many impatient "throw -away" comments, cheap-shots that so lower the tone of the discourse. One is often left puzzling as to the ground of these comments. For example, in the infamous footnote 351, he lectures priests that "the confessional must not be a torture chamber." A torture chamber?

In another example, in n. 36, he says: "We often present marriage in such a way that its unitive meaning, its call to grow in love and its ideal of mutual assistance are overshadowed by an almost exclusive insistence on the duty of procreation".

Anyone slightly acquainted with the development of doctrine on marriage, knows that the unitive good has received a great deal of renewed focus since at least "Gaudium et Spes" 49, with a back history of some decades.

To me, these impulsive, unfounded caricatures are unworthy of what should be the dignity and seriousness of an apostolic exhortation.

In nn. 121, 122, we have a perfect example of the erratic quality of Pope Francis’s discourse. At first describing marriage as "a precious sign" and as "the icon of God’s love for us", within a few lines this imaging of Christ and his Church becomes a "tremendous burden" to have to impose on spouses. He used the phrase earlier in n. 37. But who has ever expected sudden perfection of the married, who has not conceived of marriage as a lifelong project of growth in the living out of the sacrament?

Pope Francis’ language of emotion and passion (nn. 125, 242, 143, 145) owes nothing to the Fathers of the Church or the expositors of the spiritual life in the great Tradition, but rather to the mentality of the popular media. His simple conflation of eros and sexual desire in n. 151 succumbs to the secularist view of it, and ignores Pope Benedict’s "Deus Caritas Est", steeped in a thoughtful exposition of the mystery of eros and agape and the Cross.

One balks at the ambiguous language of n. 243 and n. 246, implying that somehow it is the Church’s fault, or something the Church has to be anxiously apologetic about it when her members enter upon an objectively adulterous union, and thereby exclude themselves from Holy Communion. This is a governing idea that pervades the entire document.

Several times through this document I have paused and wondered: “I haven’t heard of Christ for pages". All too often we are subjected to long tracts of homespun avuncular advice that could be given by any secular journalist without the faith, the sort of thing to be found in the pages of Reader’s Digest, or one of those Lifestyle inserts in weekend newspapers.

It is true, some doctrines of the Church are robustly upheld, e.g. against same-sex unions (n. 52) and polygamy (n. 53), gender ideology (n. 56) and abortion (n. 84); there are affirmations of the indissolubility of marriage (n. 63), and its procreative end, and an upholding of "Humanae Vitae" (nn. 68, 83), the sovereign rights of parents in the education of their children (n. 84), the right of every child to a mother and a father (nn. 172, 175), the importance of fathers (nn. 176, 177). You can even occasionally find a poetic thought, such as ‘the gaze’ of contemplative love between spouses (nn. 127-8), or the maturing of good wine as an image of the maturing of spouses (n. 135).

But all this laudable doctrine is undermined, I submit, by the overall rhetoric of the exhortation, and by that of Pope Francis’ entire papacy. These affirmations of catholic doctrine are welcome, but, it needs to be asked, do they have any more weight than that of the passing and erratic enthusiasm of the current incumbent of St Peter’s Chair? I am serious here. My instinct is that the next position threatening to crumble, will be the issue of same-sex "marriage". If it is possible to construct a justification of states of objective adultery, on the basis of recognizing "the constructive elements in those situations not yet corresponding to the Church’s teaching on marriage" (n. 292), "when such unions attain a particular stability, legally recognized, are characterized by deep affection and responsibility for their offspring" (n. 293) etc., how long can you defer applying exactly the same line or reasoning to same-sex partnerships? And yes, children may be involved, as we know very well from the gay agenda. Already, the former editor of the catholic Catechism, [Cardinal Christoph Schönborn], to whose hermeneutic of AL as a "development of doctrine", Pope Francis has referred us, appears to be "evolving" on the potential for "good" same-sex "unions".

Reading chapter eight

And all that was be fore I came to reading chapter eight. I have wondered if the extraordinary prolixity of the first seven chapters was meant to wear us down before we came to this crucial chapter, and catch us off-guard. To me, the entire tenor of chapter eight is problematic, not just n. 304 and footnote 351. As soon as I finished it, I thought to myself: Clear as a bell: Pope Francis wanted some form of the Kasper proposal from the beginning. Here it is. Kasper has won. It all explains Pope Francis’ terse comments at the end of the 2015 Synod, when he censured narrow-minded "pharisees" – evidently those who had frustrated a better outcome according to his agenda. "Pharisees"? The sloppiness of his language! They were the modernists, in a way, of Judaism, the masters of ten thousand nuances – and most pertinently, those who tenaciously upheld the practice of divorce and remarriage. The real analogues of the pharisees in this whole affair are Kasper and his allies.

To press on. The words of n. 295 on St John Paul’s comments on the "law of gradualness" in "Familiaris Consortio" 34, seem to me subtly treacherous and corruptive. For they try to co-opt and corrupt John Paul in support precisely of a situational ethics that the holy pope bent all his loving pastoral intelligence and energy to oppose. Let us hear then what St John Paul really says about the law of gradualness:

"Married people... cannot however look on the law as merely an ideal to be achieved in the future: they must consider it as a command of Christ the Lord to overcome difficulties through constancy. And so what is known as 'the law of gradualness' or step-by-step advance cannot be identified with a 'gradualness of the law', as if there were differing degrees or forms of precept in God’s law for different individuals and situations. In God’s plan, all husbands and wives are called in marriage to holiness".

Footnote 329 of "Amoris Laetitia" also presents another surreptitious corruption. It cites a passage of "Gaudium et Spes" 51, concerning the intimacy of married life. But by an undetected sleight of hand it is placed in the mouth of the divorced and remarried instead. Such corruptions surely indicate that references and footnotes, which in this document are made to do some heavy lifting, need to be properly verified.

Already in n. 297, we see the responsibility for "irregular situations" being shifted to the discernment of pastors. Step by subtle step the arguments advance definite agenda. N. 299 queries how "current forms of exclusion currently practiced" can be surmounted, and n. 301 introduces the idea of "conversation with the priest in the internal forum". Can you not already detect where the argument is going?

So we arrive at n. 301, which drops the guarded manner as we descend into the maelstrom of "mitigating factors". Here it seems the "mean old Church" has finally been superseded by the "nice new Church": in the past we may have thought that those living in "irregular situations" without repentance were in a state of mortal sin; now, however, they may not be in a state of mortal sin after all, indeed, sanctifying grace may be at work in them.

It is then explained, in an excess of pure subjectivism, that "a subject may know full well the rule, yet have great difficulty in understanding its inherent value". Here is a mitigating factor to beat all mitigating factors. On this argument then, do we now exculpate the original envy of Lucifer, because he had "great difficulty in understanding" the "inherent value" to him, of the transcendent majesty of God? At which point, I feel that we have lost all foothold, and fallen like Alice into a parallel universe, where nothing is quite what it seems to be.

A series of quotations from St Thomas Aquinas are brought to bear, on which I am not qualified to comment, except to say that, obviously, proper verification and contextualization are strongly indicated. N. 304 is a highly technical apologia for moral casuistry, argued in exclusively philosophical terms without a hint of Christ or of faith. One cannot but think that this was supplied by another hand. It is not Francis’ style, even if it is his belief.

Finally we come to the crucial n. 305. It commences with two of the sort of throwaway caricatures that recur throughout the document. The new doctrine that Pope Francis had flagged a little earlier he now repeats and reasserts: a person can be in an objective situation of mortal sin – for that is what he is speaking about – and still be living and growing in God’s grace, all the "while receiving the help of the Church", which, the infamous footnote 351 declares, can include, "in certain cases", both confession and holy communion. I am sure that there are by now many busily attempting to "interpret" all this according to a "hermeneutic of continuity", to show its harmony, I presume, with Tradition. I might add that in this n. 305, Pope Francis quotes himself four times. In fact, it appears that Pope Francis’ most frequently cited reference through "Amoris laetitia" is himself, and that in itself is interesting.

In the rest of the chapter Pope Francis changes tack. He makes an inverted admission that his approach may leave "room for confusion" (n. 308). To this he responds with a discussion of "mercy". At the very beginning in n. 7 he declared that "everyone should feel challenged by chapter eight". Yes we do, but not quite in the blithe heuristic sense he meant it. Pope Francis has freely admitted in time past that he is the sort of person who loves to make "messes"? Well, I think we can concede that he has certainly achieved that here.

Let me tell you of a rather taciturn and cautious friend, a married man, who expressed to me, before the apostolic exhortation was published: "O I do hope he avoids ambiguity". Well, I think even the most pious reading of "Amoris Laetitia" cannot say that it has avoided ambiguity. To use Pope Francis’ own words, "widespread uncertainty and ambiguity" (n. 33 ) can certainly be applied to this document, and I venture to say, to his whole papacy. If we are put into the impossible situation of critiquing a document of the ordinary magisterium, consider whether in "Amoris Laetitia" Pope Francis himself is relativizing the authority of the magisterium, by eliding the magisterium of Pope John Paul, specially in "Familiaris Consortio" and "Veritatis Splendor". I challenge any of you to soberly reread the encyclical "Veritatis Splendor", say nn. 95-105, and not conclude that there is a deep dissonance between that encyclical and this apostolic exhortation. In my younger years, I anguished over the conundrum: how can you be obedient to the disobedient? For a pope too, is called to obedience – indeed, preeminently so.

The wider implications of "Amoris Laetitia"

The serious difficulties I foresee, for priests in particular, arise from clashing interpretations of the loopholes discretely planted throughout "Amoris Laetitia". What will a young new priest do, who, well informed, wishes to maintain that the divorced and remarried can in no wise by admitted to Holy Communion, while his parish priest has a policy of "accompaniment", which on the contrary envisages that they can. What will a parish priest with a similar sense of fidelity do, if his bishop and diocese decide for a more liberal policy? What will one region of bishops do in relation to another region of bishops, as each set of bishops decides how to cut and divide the "nuances" of this new doctrine, so that in the worst case, what is held to be mortal sin on one side of the border, is "accompanied" away and condoned on the other side of the border? We know it is already happening, officially, in certain German dioceses, and unofficially in Argentina, and even here in Australia, for years, as I can vouch from my own family.

Such an outcome is so appalling, it may mark, as another friend, also a married man, suggested, the collapse of the catholic christian narrative. But of course other aspects of ecclesial and social deterioration have also brought us to this point: the havoc of pseudo-renewal in the Church in the past few decades, the numbingly stupid policy of inculturation applied to a deracinated Western culture of militant secularism, the relentless, progressive erosion of marriage and the family in society, the greater attack on the Church from within than from without that Pope Benedict so lamented, the long defection of certain theologians and laity in the matter of contraception, the frightful sexual scandals, the countless casual sacrileges, the loss of the spirit of the liturgy, the "de facto" internal schisms on a whole range of serious issues and approaches, thinly papered over with a semblance of "de jure" Church unity, the patterns of profound spiritual and moral dissonance that seethe beneath the tattered title of "catholic" these days. And we wonder that the Church is in a weakened state and fading away?

We might also trace the long diachronic antecedents of AL. Being something of an ancient soul, I see this document as the bad fruit of certain second-millennium developments in the Western Church. I briefly point to two in particular: the sharply rationalist and dualist form of Thomism fostered among the Jesuits in the 16th century, and in that context, their elaboration of the casuistic understanding of mortal sin in the 17th century. The art of casuistry was pursued in a new category of sacred science called "moral theology", in which, it seems to me, the slide-rule of calculation is skilfully plied to estimate the minimum culpability necessary to avoid the imputation of mortal sin – technically at any rate. What a spiritual goal! What a spiritual vision! Today, casuistry rears its ugly head in the new form of situational ethics, and "Amoris Laetitia", quite frankly, is full of it – even though it was expressly condemned by St John Paul II in the encyclical "Veritatis Splendor"!

Peroration

Can I exhort you in any way that can help? St Basil has a great homily on the text: "Only take heed to yourself and guard your soul diligently" (Deut 4:9). We must attend to our own dispositions first. The Desert Fathers have several stories in which a young monk secures his eternal salvation through the heroic meekness of his obedience to a seriously flawed abba. And he ends by bringing about the repentance and salvation of his abba too. We must not let ourselves be tempted into any reaction of hostility to Pope Francis, lest we become part of the devil’s game. This deeply flawed Holy Father too we must honour, and carry in charity, and pray for. With God nothing shall be impossible. Who knows whether God has got Jorge Mario Bergoglio into this position in order to find a sufficient number to pray efficaciously for the salvation of his soul?

I notice that Cardinals Sarah and Pell are silent. What wisdom there may be in that – for the time being. Meanwhile, you who have responsibilities in the governance of the Church, will have to make practical dispositions in regard to the thorny issues of "Amoris Laetitia". First of all, in our own minds, we should have no doubt teaching of the Gospel is, and ever will be. Obviously, whatever strategy of pressing for an official clarification of projected pastoral practice that can be devised, must be tried. I particularly urge this on bishops. Some of you may find yourselves in very difficult situations in regard to your peers, almost calling for the virtues of a confessor of the faith. Are you ready for the whipping, figuratively speaking, you may incur? You could of course, choose the illusory safety of conventional shallowness and superficial good cheer, a great temptation of ecclesiastics as company men. I don’t advise it. The times are serious, perhaps much more serious than we suspect. We are being put to the test. "The Lord is here. He is calling you".

On the appropriate eucharistic disposition of the divorced and remarried

I lately had some email correspondence, in which a friend made some points on the worthy eucharistic dispositions of those in "irregular situations". In my reply I expressed my own thoughts on what I think is the spiritually and sacramentally advisable conduct of a Catholic who is in an "irregular situation":

There is a lovely woman who usually comes to mass in our cathedral and sits down the back. I had conversation with her, and learned she was in one of these "irregular situations", but is still very diligent in coming to mass, but does not partake of holy communion. She does not rail against the Church, or say "It’s the Church’s fault", or "How unjust the Church is!", which sentiments indeed I have heard from others, and gently called to order. I find this woman’s conduct admirable in the circumstances.

The best stance in prayer for those who are in these situations and cannot as yet bring themselves to the measure of repentance required (and so to confession), but who do not want to let go of looking God-ward, is to present themselves to the Lord at mass precisely in their state of privation and need, not going forward to "grasp" the eucharist, but endeavoring to lay themselves open to the intervention of grace and a change of circumstances, if and when it be possible. My sense of their plight is: it is better that they hold themselves honestly, if painfully, in the tension of their situation before God, without subterfuge. I think this is to position themselves best for the triumph of grace.

Who of us cannot identify with this unequal situation in the spiritual contest of our own life, i.e. of battling hard with some seemingly intractable passion, and scarcely finding our way out of it, or perhaps being bogged down a long time in some sin before our moral life emerges into a place of greater freedom? Remember Augustine’s famous prayer to God in the lead-up to his definitive conversion: "Domine, da mihi castitatem, sed noli modo": O Lord, give me chastity. but not yet? I think that when such people attend mass and refrain from taking communion, it is potentially a great witness to all of us. And yes, it does cry out to us to consider our own dispositions in going forward to partake of our Lord’s most holy, deifying Body and Blood.

Apropos of which, it occurs to me to report a saying of the actor Richard Harris, a "hell-raiser" of a lapsed catholic for many a year: "I’m divorced twice, but I would prefer to die a bad catholic than have the Church change to suit me".

I find more truthfulness in that, than in... well, I had better not say it.

P.S. Some bishops are forging the way forward with bold clarity.

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Vatican I on the Purpose of Papal Primacy Definition

"And since the gates of hell trying, if they can, to overthrow the Church, make their assault with a hatred that increases day by day against its divinely laid foundation, we judge it necessary, with the approbation of the Sacred Council, and for the protection, defense and growth of the Catholic flock, to propound the doctrine concerning the 1. institution, 2. permanence and 3. nature of the sacred and apostolic primacy, upon which the strength and coherence of the whole Church depends." Pastor Aeternus, introduction, paragraph 6.

Pope Francis (and his theologians) appears to disagree with that solemnly defined nature and mission of the Church and of the papacy, but his disagreement, since not ex cathedra, is not infallible. On this he is clearly wrong (regardless of everything else he might have right).

More on Vatican I and the extent and limits of papal infallibility later.

Friday, June 10, 2016

Cardinal Müller Calls Out Heretic Pope Francis Ghostwriter

In an interview published in the most recent issue of "Herder Korrespondenz" the Prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, His Eminence Cardinal Gerhard L. Müller, states that His Excellency Archbishop Víctor Manuel Fernández', Rector of the Catholic University of Buenos Aires (which rectorship he assumed in 2009 given to him by Cardinal Bergoglio, but only finally confirmed in 2011 after answering some doubts by the CDF regarding the doctrinal content of some of his published articles; he was also named Archbishop by the same Bergoglio, Pope Francis, May 13, 2013) published opinion regarding the Papacy is heresy. Cf. Sandro Magister's article today.

The same Archbishop Fernández is the apparent ghostwriter (which he publicly admits) of the confused pen of the Pontiff. E.g. his "situation ethics" background and Amoris Laetitia.

Well done Your Eminence Cardinal Müller! It is, after all, the job of the Prefect of the CDF to protect the doctrine of the faith wherever it is threatened. Perhaps His Eminence should remove the Archbishop from his position at the Catholic University!

Thursday, June 9, 2016

The Masculine Genius

Doctor Deborah Savage speaks of the distinctive charism of men, from the beginning.

Just saw this this morning. Hope she writes a book, with a strong Thomist bent, to answer the present questions in this area.

What does it mean to be a man? How do men uniquely image God? And why is it so necessary for families, cultures, and the Church that men live the truth of their masculinity?

Dr. Deborah Savage, professor of theology and philosophy at St. Paul’s Seminary School of Divinity, will address these questions and more in this discussion about the growing crisis in masculinity and the “masculine genius” led by host Michael Hernon, vice president of Advancement at Franciscan University, and panelists Dr. Regis Martin and Dr. Scott Hahn of Franciscan University’s Theology Department.

Air dates:

Sunday, June 5, 10:00 p.m.

Thursday, June 9, 5:00 a.m.

Saturday, June 11, 1:00 a.m.

Just saw this this morning. Hope she writes a book, with a strong Thomist bent, to answer the present questions in this area.

What does it mean to be a man? How do men uniquely image God? And why is it so necessary for families, cultures, and the Church that men live the truth of their masculinity?

Dr. Deborah Savage, professor of theology and philosophy at St. Paul’s Seminary School of Divinity, will address these questions and more in this discussion about the growing crisis in masculinity and the “masculine genius” led by host Michael Hernon, vice president of Advancement at Franciscan University, and panelists Dr. Regis Martin and Dr. Scott Hahn of Franciscan University’s Theology Department.

Air dates:

Sunday, June 5, 10:00 p.m.

Thursday, June 9, 5:00 a.m.

Saturday, June 11, 1:00 a.m.

The Full Paper is Here

"Now, I would never really question the Pope and I would follow whatever direction Pope Francis gives, but I actually don't think its a good idea to pursue a theology of women. I'm not really sure what that would mean anyway...If he calls [me] I will tell him that what we need is a theology of complementarity."

Below is a handout that goes with the talk, available at faithandreason.com.

Deborah Savage January 2015 Franciscan University Presents

“The Masculine Genius” Dr. Deborah Savage Is There a Masculine Genius?

When Pope St. John Paul II wrote his Apostolic Letter On the Dignity and Vocation of Women in 1988, he introduced into the Catholic tradition an entirely new category in the Church’s understanding of the human person: the so-called “feminine genius.” In that document, St. John Paul declares that woman’s genius is expressed in her unique yet natural tendency to attend, above all, to persons. He argues that this genius is grounded in the fact that all women possess the capacity to be mothers in either a physical or spiritual sense. And it is a quality that is found most perfectly in Mary, the Mother of God. Since then, there has been much interest in these new insights and a great deal of faithful reflection on the significance and place women occupy in both the Church and society. The genius of women, as well as John Paul’s teaching on the complementarity that characterizes the relationship of man and woman, have become an integral part of the Church’s magisterial teaching and tenets of Catholic doctrine. Most recently, Pope Francis has called for a “theology of women,” reflecting the Church’s ongoing concern for these questions and her wish to affirm the contributions of women to community life. And this is all to the good. But if we wish to arrive at a fuller account of the complementarity of men and women, it seems time to ask the obvious question: is there not also a masculine “genius”? And if so, what might that be? First, let’s be clear – there most definitely is a masculine genius. We witness it every day in the presence of fathers in family life and the contributions made by men of all ages to our communities. What is missing is a deeper understanding of what that genius really is and where it originates. And as it turns out, another look at Genesis 2 reveals a point of departure for an account, not only of the feminine genius, but the masculine genius as well. An initial point of interest is the fact that man encounters God first and is alone with Him in the Garden for some time, something that has implications for man’s role as head of the family. But also notable is that man’s first contact with reality is clearly of a horizon that otherwise contains only lower creatures, what we might call “things”; this is what leads God to conclude that the man is alone, and ultimately leads to the building of woman. But in the first instance, man is surrounded by the “things” God has made - and then tasked with naming all the creatures God brings him as they search for a suitable partner for him. It is in naming them that he takes dominion over them. St. Thomas Aquinas went so far as to argue that Adam must have received a distinct preternatural gift, a special kind of infused knowledge, which made it possible for him to name the goods of creation. It is here that we find the source and proper context of man’s well Deborah Savage January 2015 documented (and often ridiculed) natural tendency to attend to things. It is found in the Scriptural account of the first man. And it is his special genius. Even more revealing, it is man who, at Genesis 2:15, is put in the garden to “till it,” well before the fall puts him at odds with creation. This is his work. And his knowledge of “things” serves him well as he goes about his work there. Thus to this genius, we can credit the survival of the human species, the building up of civilizations, and the preservation of families throughout the history of mankind. The radical feminist movement would have you believe otherwise, but the truth is, if it weren’t for men, we would still be living in grass huts. The men in our lives are usually tireless workers (like St. Joseph) who have an amazing gift for taking the gifts of creation and putting them at the service of their families, their communities, the world. They deserve our gratitude and our respect. But this should not be taken to mean that man is oriented only toward things. When the woman is brought to him, though he also names her, he knows immediately that she is not an object; she is a person. For upon encountering her, he says “This at last is bones of my bones, flesh of my flesh.” Through his encounter with the woman, the Lord God reveals to him the nature of the reciprocal relationship of the gift of self. And man must realize as well that his own gift – that of caring for and using the goods of creation – is a gift to be exercised in service to her authentic good and in their joint mission to have dominion over all the earth. A brief word concerning the source of the feminine genius is necessary here because, though certainly St. John Paul II is right – that the maternal nature of woman is an expression of her genius – there is actually a prior point of departure for that reality. And it is found when we recognize that woman’s first contact with reality is of a horizon that, from the beginning, includes man, that is, it includes persons. Upon seeing Adam, Eve recognizes another like her, an equal, while the other creatures and things around her appear only on the periphery of her gaze. Thus, in addition to her capacity to conceive and nurture human life, indeed prior to it, woman’s place in the order of creation reveals that, from the beginning, the horizon of all womankind includes persons, includes the other. The genius of woman is found here. While man’s first experience of his own existence is of loneliness, woman’s horizon is different, right from the start. From the first moment of her own reality, woman sees herself in relation to the other. And woman is to keep constantly before us the fact that the existence of living persons, whether in the womb or walking around outside of it, cannot be forgotten, while we frantically engage in the tasks of human living. Woman is responsible for reminding us all that all human activity is to be ordered toward authentic human flourishing. Of course, the fall changed everything and these two complementary gifts only reach their full expression through the saving action of Christ and full participation in the life of grace. But, as the Church teaches, it is this very complementarity that gives man and woman their mission – to create, not only human families, but human history itself. It is only together that woman and man can fulfill their destiny – to return all things to Christ.

—Originally published in The Catholic Servant, P.O. Box 24142, Minneapolis, MN 55424, catholicservant.org.

—Originally published in The Catholic Servant, P.O. Box 24142, Minneapolis, MN 55424, catholicservant.org.

Titles Mentioned on Franciscan University Presents “The Masculine Genius” with guest, Dr. Deborah Savage

Mulieris Dignitatem (Apostolic Letter, “On the Dignity and Vocation of Women”) by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Mulieris Dignitatem (Apostolic Letter, “On the Dignity and Vocation of Women”) by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Boys Adrift: The Five Factors Driving the Growing Epidemic of Unmotivated Boys and Underachieving Young Men by Leonard Sax. Basic Books. Available on www.amazon.com.

The Nuptial Mystery by Angelo Cardinal Scola. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. Available on www.amazon.com.

Casti Connubii (Papal Encyclical, “On Christian Marriage”) by Pope Pius XI. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Letter to Women by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Christifideles Laici (Apostolic Exhortation, “On the Vocation and the Mission of the Lay Faithful”) by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

The Nuptial Mystery by Angelo Cardinal Scola. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. Available on www.amazon.com.

Casti Connubii (Papal Encyclical, “On Christian Marriage”) by Pope Pius XI. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Letter to Women by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

Christifideles Laici (Apostolic Exhortation, “On the Vocation and the Mission of the Lay Faithful”) by Pope John Paul II. Available online on www.vatican.va.

For the free handout mentioned during the show, visit FaithandReason.com or contact us at presents@franciscan.edu or 1-888-333-0381.

View previously aired episodes of Franciscan University Presents at FaithandReason.com. Academically Excellent, Passionately Catholic Steubenville, Ohio, USA 1-800-783-6220, Franciscan.edu.

N.B.

Deborah Savage, "The Genius of Man," Thinking with Pope Francis: Catholic Women Reflect on Complementarity, Feminism and the Church, OSV Press, February 2015.

"The Nature of Woman in Relation to Man"

"Women's Work"

View previously aired episodes of Franciscan University Presents at FaithandReason.com. Academically Excellent, Passionately Catholic Steubenville, Ohio, USA 1-800-783-6220, Franciscan.edu.

N.B.

Deborah Savage, "The Genius of Man," Thinking with Pope Francis: Catholic Women Reflect on Complementarity, Feminism and the Church, OSV Press, February 2015.

"The Nature of Woman in Relation to Man"

"Women's Work"

Wednesday, June 8, 2016

Tuesday, June 7, 2016

Motu Proprio with Broad (Vague) Scope for the Removal of Bishops for "Negligence"

"The Pope’s move to hold bishops accountable could have seismic consequences"

The potential scope of the new definition of episcopal negligence is of huge significance

posted Saturday, 4 Jun 2016

This morning, Pope Francis issued the motu proprio Come una madre amorevole [June 4, 2016], or As a loving mother. The letter establishes the long-awaited procedural norms for the removal of diocesan bishops for negligence in cases involving clerical sexual abuse, which were first announced last year.

Canon law, as the new norms acknowledge, already provides for the loss of any ecclesiastical office, including that of a diocesan bishop, for “grave cause” (cc. 192-193); Come una madre makes explicit that negligence in the exercise of their office is such a grave cause, especially when linked to cases of clerical sexual abuse.

According to the new norms, the appropriate Congregation of the Roman Curia will conduct the entire process of investigating a bishop themselves: they will determine which cases to investigate, gather evidence, meet other bishops from the relevant territory, and hear the defence of the accused before reaching their conclusion as part of the Congregation’s business when meeting in ordinary session. If they find in favour of removal, the decision must be approved by the Pope personally, who will be assisted by a special legal advisory group in these cases.

The new norms themselves are, as law, minimalistic, and I expect there will be further developments and clarifications. As an example, they establish that the process of investigating and removing a bishop is instigated and carried out by the “competent Congregation of the Roman Curia”, though which congregation is not explicitly clear in the legal text.

According to the “Five Point Plan” approved by Pope Francis a year ago, and which began this process, the Congregation for Bishops, or, when appropriate, occasionally the Congregations for the Evangelisation of Peoples or Oriental Churches, would be competent to receive and investigate complaints of abuse of office made against a bishop.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith would be competent to handle cases of abuse of office when they were connected to the abuse of minors, and there was going to be a new Judicial Section established within the CDF. It is not clear if this is still the intended distribution of competence, and there is no mention of a Judicial Section for the CDF inCome una madre, only of a “special college of jurists” who will help the Pope make the final determination in each case; what form this college will take, and what Congregation it will exist within, are yet to be announced.

While the legal minutiae will, no doubt, be made clear, there is already some confusion about the basic character of the new procedures. It is clear enough that the new process is administrative, rather than judicial, but, in presenting the motu proprio, Fr Federico Lombardi claimed that it was “not a penal procedure” because it concerned cases of “negligence” rather than “crime”. It is possible Fr Lombardi was speaking off the cuff and without proper legal briefing, but his words have come as a surprise to canonists, since sufficiently culpable negligence is established as a crime in the Code of Canon Law in canon 1389 §2.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the reforms, and the one which could prove to be the most seismic in its application, is that it establishes that negligence by a bishop which causes serious harm, either to an individual or to the community, can result in his being removed from office. This harm can be physical, moral, or spiritual, and it does not have to be linked, per se, to instances of child sexual abuse, though that will undoubtably be foremost in the new norms’ intention.

The potential scope of this new definition of episcopal negligence is of huge significance. Under these new norms, bishops could see cases brought against them for failures in financial oversight, personnel policy or virtually any area of diocesan governance which could potentially cause “physical, moral, or spiritual harm” to an individual or the community.

On the specific issue of the handling of complaints of sexual crimes against priests, in the wake of the more horrific revelations of cover-ups in some dioceses, some bishops have taken public pride in their “swift and decisive action” following any allegation made against a priest; those priests who have been subsequently found innocent but seen their reputations ruined by summary justice may well have a case to bring.

Traditionally, the bishop in his diocese has been, almost literally, a law unto himself. Recovering the dignity and authority of that office from encroaching centralisation towards Rome was a key theme of the reforms of Vatican Council II. While the reasons he has done so are obvious and compelling, Pope Francis, for all his emphasis on synodality, has, for good or for ill, just dealt a major blow to the independence of the average diocesan bishop.

Apostolic Logic of Angels, Saints and Men on Earth

|

| 40 Hours of Adoration at the Brompton Oratory |

To [God], we owe the service which in Greek is called λατρεία, whether this be expressed through certain sacraments or performed within our own selves...

We are taught to love this good with all our hearts, with all our mind and with all our strength. We ought to be led to this good by those who love us, and we ought to lead those whom we love to it. Thus are fulfilled those two commandments upon which hang all the Law and the prophets: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy hear and with all thy mind and with all thy soul;" and "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself." Matt. 22:37 ff. For in order that man may know what it is to love himself, an end has been appointed for him to which he is to refer all that he does, so that he may be blessed; for he who loves himself desires nothing else than to be blessed. And this end is attained by drawing near to God. And so, when one who already knows what it is to love himself is commanded to love his neighbor as himself, what else is being commanded than that he should do all that he can to encourage his neighbor to love God? This is the worship of God; this is true religion; this is right piety; this is the service which is due to God alone.

If any immortal power, then, no matter how great the virtue with which it is endowed, loves us as itself (e.g. the Angels and the Saints in heaven), it must desire that we find our blessedness by submitting ourselves to Him, in submission to Whom it finds its own blessedness. If such a power does not worship God, it is miserable because deprived of God. If, however, it does worship God, it does not desire to be worshiped in place of God. Rather, it confirms and sustains with all the strength of its love that divine decree in which it is written: "He that sacrificeth unto any god, save unto the Lord only, he shall be utterly destroyed." Exod. 22:20.

The City of God, Saint Augustine, Book X, Chapter 3, edited by R.W. Dyson, Cambridge University Press, 1998, 394-396.

P.S. In heaven there is no divided allegiance! All worship the Lord and the Lord alone. That is the Catholic faith.

The Secular Humanist Purports to Men What He Claims Impossible for God

They claim more for man than they will allow for God. If unattended man can reach the heights (which is not self-evident), why cannot God reach the (our) depths? which is the object of faith.

In other words, they claim that men may become gods, but that God could not become man!

Humility for confession and trust is the remedy. Pride, vain pride, is the problem of unbelief, for those who do not believe God, believe myriad lesser things.

The gospel of that worldly metaphysics would say: "For God it is impossible, but not for man. For man all things are possible." They invert reality. Nietzsche's Übermensch is a phantom of his imagination and of his pride!

Cf. City of God, Saint Augustine, Book X, Chapter 29, 2.

Cf. City of God, Saint Augustine, Book X, Chapter 29, 2.

But to be able to acquiesce to this truth, humility was necessary, to which it is extremely difficult to bend you. For what is there incredible, especially to men like you, accustomed to speculation, which might have predisposed you to believe in this—what is there incredible, I say, in the assertion that God assumed a human soul and body? You yourselves ascribe such excellence to the intellectual soul, which is, after all, the human soul, that you maintain that it can become consubstantial with that intelligence of the Father whom you believe in as the Son of God. What incredible thing is it, then, if some one soul be assumed by Him in an ineffable and unique manner for the salvation of many? Moreover, our nature itself testifies that a man is incomplete unless a body be united with the soul. This certainly would be more incredible, were it not of all things the most common; for we should more easily believe in a union between spirit and spirit, or, to use your own terminology, between the incorporeal and the incorporeal, even though the one were human, the other divine, the one changeable and the other unchangeable, than in a union between the corporeal and the incorporeal. But perhaps it is the unprecedented birth of a body from a virgin that staggers you? But, so far from this being a difficulty, it ought rather to assist you to receive our religion, that a miraculous person was born miraculously. Or, do you find a difficulty in the fact that, after His body had been given up to death, and had been changed into a higher kind of body by resurrection, and was now no longer mortal but incorruptible, He carried it up into heavenly places? Perhaps you refuse to believe this, because you remember that Porphyry, in these very books from which I have cited so much, and which treat of the return of the soul, so frequently teaches that a body of every kind is to be escaped from, in order that the soul may dwell in blessedness with God. But here, in place of following Porphyry, you ought rather to have corrected him, especially since you agree with him in believing such incredible things about the soul of this visible world and huge material frame. For, as scholars of Plato, you hold that the world is an animal, and a very happy animal, which you wish to be also everlasting. How, then, is it never to be loosed from a body, and yet never lose its happiness, if, in order to the happiness of the soul, the body must be left behind? The sun, too, and the other stars, you not only acknowledge to be bodies, in which you have the cordial assent of all seeing men, but also, in obedience to what you reckon a profounder insight, you declare that they are very blessed animals, and eternal, together with their bodies. Why is it, then, that when the Christian faith is pressed upon you, you forget, or pretend to ignore, what you habitually discuss or teach? Why is it that you refuse to be Christians, on the ground that you hold opinions which, in fact, you yourselves demolish? Is it not because Christ came in lowliness, and you are proud? The precise nature of the resurrection bodies of the saintsmay sometimes occasion discussion among those who are best read in the Christian Scriptures; yet there is not among us the smallest doubt that they shall be everlasting, and of a nature exemplified in the instance of Christ's risen body. But whatever be their nature, since we maintain that they shall be absolutely incorruptible and immortal, and shall offer no hindrance to the soul's contemplation, by which it is fixed in God, and as you say that among the celestials the bodies of the eternally blessed are eternal, why do you maintain that, in order toblessedness, every body must be escaped from? Why do you thus seek such a plausible reason for escaping from the Christian faith, if not because, as I again say, Christ is humble and you proud? Are you ashamed to be corrected? This is the vice of the proud. It is, forsooth, a degradation for learned men to pass from the school ofPlato to the discipleship of Christ, who by His Spirit taught a fisherman to think and to say, In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by Him; and without Him was not anything made that was made. In Him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shines in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not. John 1:1-5 The old saint Simplicianus, afterwards bishop of Milan, used to tell me that a certain Platonist was in the habit of saying that this opening passage of the holy gospel, entitled, According to John, should be written in letters of gold, and hung up in all churches in the most conspicuous place. But the proud scorn to take God for their Master, because the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us. John 1:14 So that, with these miserable creatures, it is not enough that they are sick, but they boast of their sickness, and are ashamed of the medicine which could heal them. And, doing so, they secure not elevation, but a more disastrous fall.

Spiritual Because Religious

Our religion is not a "spiritual" religion, it is a human religion. It is integrally human precisely because it is divine; and is it not more human for the soul, once purified, to be able to re-assume in it's place, in association with it's ecstasy, the body, which here below it tried in vain to lead to happiness? Our religion is founded on the incarnation, I tell you, not on dis-incarnation. The visibility of the Church, its social character, its sacamental means, all of its practice, witness to its character. The resurrection of the dead is a corollary called for by doctrinal coherence as by the very nature of things. United, in the Church, to the Spirit of Christ, forming "body" with Christ, we have a right, at our hour, to take part in the resurrection of Christ and in the triumph of his mortal flesh. "If the Spirit which resurrected the Lord Jesus lives in you, He will also revive your mortal bodies." (Saint Paul)

Catchisme des Incroyants, vol II, A.D. Sertillanges, Flamarrion, 1930, 246.

Monday, June 6, 2016

Muhammad Ali Apostate Witnesses to God and to Eternity: RIP

Cassius Clay ("Muhammad Ali") was a Christian apostate, rejecting the Christian faith of his youth to go to the anti-Christian religion of Muhammadism, to which he has drawn many Christians (including various wives, one of whom was Catholic). He had nine children from six different women. An icon of the novel and widespread African-American rejection of Jesus Christ, in a distorted sense of freedom. Their young men (often reared Christians, like Ali himself, and in the context of prison) are being led to believe that an Arabian war lord is to be preferred to the Prince of Peace!

What the misguided American Muhammanden black man fails to realize is that Jesus Christ is God, the Savior of the world, Africa and Afro-America included. There are 175 million Catholics in Africa right now, and growing. Christianity was in Africa for five centuries before Muhammad was even born, and it will be there long after that false religion is gone. Mr. Ali, an apostate leader, is hardly a hero. May Jesus Christ the Lord have mercy on his soul and wipe out the great and enduring scandal of his apostasy. Requiescat in pace!

Sunday, June 5, 2016

The Son of the Widow of Nain: Luke 7:11-17

Saint Augustine's Sermon 98 is on today's gospel passage from the novus ordo mass, and on the three (types of) people Christ raises from the dead.

Español

Latin

Friday, June 3, 2016

The Street Flows into the Sanctuary

That is my assessment of the present state of the Catholic "ordinary form" liturgy. Casual, at best, and often banal and even crude. Offensive and often opposed to traditional Catholic piety. E.g., talking in church precludes quiet recollection there; our confessionals have become broom closets! Often the city street is more agreeable to quiet mental prayer than the busy holy sanctuary; and there are more confessions in bars and barber shops than in church!

Cf. Iam pridem Syrus in Tiberim defluxit Orontes. Juvenal, Satires 3:62.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

أسماء الله الحسنى Islam's Prayer Beads: The Ninety Nine Names of God

Allah (الله) The Greatest Name

1 Ar-Rahman (الرحمن) The All-Compassionate

2 Ar-Rahim (الرحيم) The All-Merciful

3 Al-Malik (الملك) The Absolute Ruler

4 Al-Quddus (القدوس) The Pure One

5 As-Salam (السلام) The Source of Peace

6 Al-Mu'min (المؤمن) The Inspirer of Faith

7 Al-Muhaymin (المهيمن) The Guardian

8 Al-Aziz (العزيز) The Victorious

9 Al-Jabbar (الجبار) The Compeller

10 Al-Mutakabbir (المتكبر) The Greatest

11 Al-Khaliq (الخالق) The Creator

12 Al-Bari' (البارئ) The Maker of Order

13 Al-Musawwir (المصور) The Shaper of Beauty

14 Al-Ghaffar (الغفار) The Forgiving

15 Al-Qahhar (القهار) The Subduer

16 Al-Wahhab (الوهاب) The Giver of All

17 Ar-Razzaq (الرزاق) The Sustainer

18 Al-Fattah (الفتاح) The Opener

19 Al-`Alim (العليم) The Knower of All

20 Al-Qabid (القابض) The Constrictor

21 Al-Basit (الباسط) The Reliever

22 Al-Khafid (الخافض) The Abaser

23 Ar-Rafi (الرافع) The Exalter

24 Al-Mu'izz (المعز) The Bestower of Honors

25 Al-Mudhill (المذل) The Humiliator

26 As-Sami (السميع) The Hearer of All

27 Al-Basir (البصير) The Seer of All

28 Al-Hakam (الحكم) The Judge

29 Al-`Adl (العدل) The Just

30 Al-Latif (اللطيف) The Subtle One

31 Al-Khabir (الخبير) The All-Aware

32 Al-Halim (الحليم) The Forbearing

33 Al-Azim (العظيم) The Magnificent

34 Al-Ghafur (الغفور) The Forgiver and Hider of Faults

35 Ash-Shakur (الشكور) The Rewarder of Thankfulness

36 Al-Ali (العلى) The Highest

37 Al-Kabir (الكبير) The Greatest

38 Al-Hafiz (الحفيظ) The Preserver

39 Al-Muqit (المقيت) The Nourisher

40 Al-Hasib (الحسيب) The Accounter

41 Al-Jalil (الجليل) The Mighty

42 Al-Karim (الكريم) The Generous

43 Ar-Raqib (الرقيب) The Watchful One

44 Al-Mujib (المجيب) The Responder to Prayer

45 Al-Wasi (الواسع) The All-Comprehending

46 Al-Hakim (الحكيم) The Perfectly Wise

47 Al-Wadud (الودود) The Loving One

48 Al-Majid (المجيد) The Majestic One

49 Al-Ba'ith (الباعث) The Resurrector

50 Ash-Shahid (الشهيد) The Witness

51 Al-Haqq (الحق) The Truth

52 Al-Wakil (الوكيل) The Trustee

53 Al-Qawiyy (القوى) The Possessor of All Strength

54 Al-Matin (المتين) The Forceful One

55 Al-Waliyy (الولى) The Governor

56 Al-Hamid (الحميد) The Praised One

57 Al-Muhsi (المحصى) The Appraiser

58 Al-Mubdi' (المبدئ) The Originator

59 Al-Mu'id (المعيد) The Restorer

60 Al-Muhyi (المحيى) The Giver of Life

61 Al-Mumit (المميت) The Taker of Life

62 Al-Hayy (الحي) The Ever Living One

63 Al-Qayyum (القيوم) The Self-Existing One

64 Al-Wajid (الواجد) The Finder

65 Al-Majid (الماجد) The Glorious

66 Al-Wahid (الواحد) The Unique, The Single

67 Al-Ahad (الاحد) The One, The Indivisible

68 As-Samad (الصمد) The Satisfier of All Needs

69 Al-Qadir (القادر) The All Powerful

70 Al-Muqtadir (المقتدر) The Creator of All Power

71 Al-Muqaddim (المقدم) The Expediter

72 Al-Mu'akhkhir (المؤخر) The Delayer

73 Al-Awwal (الأول) The First

74 Al-Akhir (الأخر) The Last

75 Az-Zahir (الظاهر) The Manifest One

76 Al-Batin (الباطن) The Hidden One

77 Al-Wali (الوالي) The Protecting Friend

78 Al-Muta'ali (المتعالي) The Supreme One

79 Al-Barr (البر) The Doer of Good

80 At-Tawwab (التواب) The Guide to Repentance

81 Al-Muntaqim (المنتقم) The Avenger

82 Al-'Afuww (العفو) The Forgiver

83 Ar-Ra'uf (الرؤوف) The Clement

84 Malik-al-Mulk (مالك الملك) The Owner of All

85 Dhu-al-Jalal wa-al-Ikram (ذو الجلال و الإكرام) The Lord of Majesty and Bounty

86 Al-Muqsit (المقسط) The Equitable One

87 Al-Jami' (الجامع) The Gatherer

88 Al-Ghani (الغنى) The Rich One

89 Al-Mughni (المغنى) The Enricher

90 Al-Mani'(المانع) The Preventer of Harm

91 Ad-Darr (الضار) The Creator of The Harmful

92 An-Nafi' (النافع) The Creator of Good

93 An-Nur (النور) The Light

94 Al-Hadi (الهادي) The Guide

95 Al-Badi (البديع) The Originator

96 Al-Baqi (الباقي) The Everlasting One

97 Al-Warith (الوارث) The Inheritor of All

98 Ar-Rashid (الرشيد) The Righteous Teacher

99 As-Sabur (الصبور) The Patient One

Pastoral Guidelines for Implementing Amoris Lætitia: Archbishop Charles J. Chaput

The Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Lætitia completes the reflection on the family conducted by the Synods of 2014 and 2015, a reflection that engaged the entire world Church. In issuing Amoris Lætitia, Pope Francis once again calls the church to renew and intensify the Christian missionary proclamation of God's mercy, while presenting more persuasively the Church's teaching about the nature of the family and the sacrament of Matrimony. In all of this the Holy Father, in union with the whole Church, hopes to strengthen existing families, and to reach out to those whose marriages have failed, including those alienated from the life of the Church.

Amoris Lætitia therefore calls for a sensitive accompaniment of those with an imperfect grasp of Christian teaching on marriage and family life, who may not be living in accord with Catholic belief, and yet desire to be more fully integrated into Church life, including the sacraments of Penance and Eucharist.

The Holy Father's text builds on the classic Catholic understanding, key to moral theology, of the relationship between objective truth about right and wrong --for example, the truth about marriage revealed by Jesus himself--and how the individual person grasps and applies that truth to particular situations in his or her judgment of conscience. Catholic teaching makes clear that the subjective conscience of the individual can never be set against the objective moral truth, as if conscience and truth were two competing principles for moral decision-making.

As St. John Paul II wrote, such a view would "pose a challenge to the very identity of the moral conscience in relation to human freedom and God's law....Conscience is not an independent and exclusive capacity to decide what is good and what is evil' (Veritatis Splendor 56, 60). Rather, "conscience is the application of the law to a particular case" (Veritaties Splendor 59). Conscience stands under the objective moral law and should be formed by it, so that [t]he truth about moral good, as that truth is declared in the law of reason, is practically and concretely recognized by the judgment of conscience" (Veritatis Spendor 61).

But since well-meaning people can err in matters of conscience, especially in a culture that is already deeply confused about complex matters of marriage and sexuality, a person may not be fully culpable for acting against the truth. Church ministers, moved by mercy, should adopt a sensitive pastoral approach in all such situations--an approach that is both patient and confident in the saving truth of the Gospel and the transforming power of God's grace, trusting in the words of Jesus Christ, who promises that "you will know the truth, and the truth will make you free (Jn. 8:32)." Pastors should strive to avoid both a subjectivism that ignores the truth and a rigorism that lacks mercy.

As Amoris Lætitia notes, bishops must arrange for the accompaniment of estranged and hurting persons with guidelines that faithfully reflect Catholic belief [Synod Final Report 85]. What follows is a template to assist those preparing such guidelines. It is meant for priests and deacons, seminarians and lay persons who work in the fields of marriage, sacramental ministry and pastoral care regarding matters of human sexuality.

For Catholic Married Couples

Christian, marriage, by its nature, is permanent, monogamous and open to life. The sexual expression of love within a truly Christian marriage is blessed by God and a powerful bond of beauty and joy between man and woman. Jesus himself raised marriage to new dignity. Every marriage of two baptized persons has access, through the sacrament of Matrimony, to grace and life in Christ, especially through the shared privilege of bringing new life into the world and raising children in the knowledge of God.

Marriage and child-rearing are sources of great joy; marriage includes moments (like the birth of a child) when the presence of God is palpable. But an intimately shared life can also cause stress and suffering. Marital fidelity is an ongoing encounter with reality. Thus it involves real sacrifices and the discipline of subordinating one's own desires to one's duties to others.

Pastors should stress the importance of common prayer and reading Scripture in the home, the grace of frequent Penance and Communion, and the need for building mutual support with committed Catholic friends and family. Every family is a "domestic church," but no Christian family can survive indefinitely without encouragement from other believing families. The Christian community must especially find ways to engage and help families who are burdened by illness, financial setbacks, and marital frictions.

For Catholics and Christians who are Separated or Divorced and Not Remarried

Pastors often encounter persons whose marriages face grave hardships, sometimes for reasons that seem undeserved, and sometimes through the fault of one or both married parties. The state of being separated or divorced, and thus finding oneself alone, can involve great pain. It can mean separation from one's children, a life without conjugal intimacy, and for some the prospect of never having children. Pastors should offer these persons friendship, understanding, introductions to reliable lay mentors, and practical help so they can sustain their fidelity even under pressure.

Likewise, parishes should be keenly concerned for the spiritual good of those who find themselves separated or divorced for a long time. Some persons, aware that a valid marriage bond is indissoluble, consciously refrain from a new union and devote themselves to carrying out their family and Christian duties. They face no obstacle to receiving Communion and other sacraments. Indeed, they should receive the sacraments regularly, and they deserve the warm support of the Christian community since they show extraordinary fidelity to Jesus Christ. God is faithful to them even when their spouses are not, a truth fellow Catholics should reinforce.

In some cases, one can reasonably ask whether an original marriage bond was valid, and thus whether grounds may exist for a decree of nullity (an "annulment"). In our age such grounds are not uncommon. This inquiry should always be guided by the truth of the situation: Did a valid marriage exist? Decrees of nullity are not an automatic remedy or an entitlement. Such matters require Church ministers to be both compassionate and alert to the truth. They should investigate these matters in a timely way, respecting the right of all parties and ensuring that all have access to the annulment process.

For Catholics and Christians who are Divorced and Civilly-Remarried

Amoris Lætitia is clearly concerned about divorced and civilly-remarried Catholics. In some cases, a valid first marriage bond may never have existed. A canonical investigation of the first marriage may be appropriate. In other cases, the first marriage bond of one or both of the civilly-remarried persons may be valid. This would impede any attempt at a second marriage. Children may further complicate the circumstances.

The divorced and civilly-remarried should be welcomed by the Catholic community. Pastors should ensure that they do not consider themselves as "outside" the Church. On the contrary, as baptized persons, they can (and should) share in her life. They are invited to attend Mass, to pray, to take part in the activities of the parish. Their children--whether from an original marriage or from their current relationship--are integral to the life of the Catholic community, and they should be brought up in the faith. Couples should sense from their pastors, and from the whole community, the love they deserve as person made in the image of God and as fellow Christians.

At the same time, as the Synod Final Report notes, priests should "accompany such people in helping them understand their situation according to the teaching of the Church and the guidelines of the Bishop. Useful in the process is an examination of conscience through moments of reflection and penance. The divorced and remarried should ask themselves: how they have acted toward their children when the conjugal union entered into crisis; if they made attempts at reconciliation; what is the situation of the abandoned party; what effect does the new relationship have on the rest of the family and the community of the faithful; and what example is being set for young people who are preparing for marriage" [Synod Final Report 85]. The Synod fathers continue: "The path of accompaniment and discernment guides the faithful to an awareness of their situation before God....[T]his discernment can never prescind from the Gospel demands of truth and charity as proposed by the Church" [Synod Final Report 86].

In light of this, priests must help the divorced and civilly-remarried to form their consciences according to the truth. This is a true work of mercy. It should be undertaken with patience, compassion, and a genuine desire for the good of all concerned, sensitive to the wounds of each person, and gently leading each toward the Lord. Its purpose is not condemnation, but the opposite: a full reconciliation of the person with God and neighbor, and restoration to the fullness of visible communion with Jesus Christ and the Church.

Can such individuals receive the sacraments? Baptized members of the Church are always in principle invited to the sacraments. The confessional's door's are always open to the contrite heart. (Where there is a canonical censure, very rarely the case in these situations, a priest-confessor can either lift the censure or help arrange for its lifting). What of Communion? Every Catholic, not only the divorced and civilly remarried, must sacramentally confess all serious sins of which he or she is aware, with a firm purpose to change, before receiving the Eucharist. In some cases, the subjective responsibility of the person for a past action may be diminished. But the person must still repent and renounce the sin, with a firm purpose of amendment.

Can such individuals receive the sacraments? Baptized members of the Church are always in principle invited to the sacraments. The confessional's door's are always open to the contrite heart. (Where there is a canonical censure, very rarely the case in these situations, a priest-confessor can either lift the censure or help arrange for its lifting). What of Communion? Every Catholic, not only the divorced and civilly remarried, must sacramentally confess all serious sins of which he or she is aware, with a firm purpose to change, before receiving the Eucharist. In some cases, the subjective responsibility of the person for a past action may be diminished. But the person must still repent and renounce the sin, with a firm purpose of amendment.In practice, pastors must convey Catholic teaching faithfully, and in a heartfelt way, to all persons--including the divorced and remarried, both in the confessional as well as publicly, and to work with people patiently as they struggle to live the teachings of Christ.

With divorced and civilly-remarried couples, the truth about marriage as the Church understands it requires abstinence from sexual intimacy. This applies even if the couple must (for the care of their children) live under one roof. The couple should approach the sacrament of Penance regularly, and seek recourse to God's mercy if they fail in chastity. Pastors should be aware that, if they give Communion to divorced and remarried persons trying to live chastely, they should seek to do so in a manner that will avoid giving scandal or implying that Church teaching can be set aside. Divorce and civil remarriage may not be given an unintended endorsement; thus divorced and remarried persons should not hold positions of responsibility in a parish (e.g. on a parish council), nor should they carry out liturgical function (e.g. lector, extraordinary minister of Holy Communion).

This is a difficult teaching for many, but anything less misleads people about the nature of the Eucharist and the Church. The grace of Jesus Christ is more than a pious cliché; it is a real and powerful seed of change in the believing heart. The lives of many saints bear witness that grace can take great sinners and, by its power of interior renewal, remake them in holiness of life. Pastors and all who work in the service of the Church should tirelessly promote hope in this saving mystery.

For Couples who Cohabit and are Unmarried

Cohabitation of unmarried couples is now common, often fueled by convenience, fear of a final commitment, or a desire to "try out" relationships. Many children are born to these irregular unions. Cohabiting and contracepting couples often enter RCIA, or seek to return to the Catholic faith, only dimly aware of the problems created by their situation.

Working with such couples, pastors should consider two issues. First, does the couple have children together? A natural obligation in justice exists for parents to care for their children. And children have a natural right to be raised by both parents. Pastors should try, to the degree possible and when a permanent commitment of marriage is viable, to strengthen existing relationships where a couple already has children together.

Second, does the couple have the maturity to turn their relationship into a permanently committed marriage? Cohabiting couples often refrain from making final commitments because one or both persons is seriously lacking in maturity or has other significant obstacles to entering a valid union. Here, prudence plays a vital role. Where one or another person is not capable of, or is not willing to commit to, a marriage, the pastor should urge them to separate.