Durandus on the Liturgical Customs of Lent

GREGORY DIPIPPO

The following selections are taken from William Durandus’ important liturgical commentary, the Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, book 6, chapter 27, which treats specifically of Ash Wednesday, but also of Lent in general. Some of the elisions here are made for the sake of a more succinct presentation of his thought; several of them are made in places where he directs the reader to matters he has discussed elsewhere in the work. The translation is my own.

After Quinquagesima follows Quadragesima, (“fortieth”, the Latin word for Lent), which is the spiritual number of penance, in which the Church fasts, and repents of its sins; for by the penance which is accomplished in Lent, we arrive at the fifty days (of Easter), which is to say, the jubilee year, which symbolizes the forgiveness of sins. Lent (Quadragesima) begins on the following Sunday, on which (the Introit) Invocavit me is sung but the fast begins on Wednesday, as will be mentioned below.

The Blessed Peter first instituted the fast of Lent before Easter. Nor is the fact that we are in abstinence for 46 days from the beginning of the fast to Easter without symbolic meaning. For after the Babylonian captivity, the temple of the Lord was built in 46 years; whence we also after the captivity of Babylon, that is, of the confusion caused by the vices, for 46 days build ourselves as a temple to God through abstinence and good works. … (“Babylon” is the Greek form of the Hebrew word “Babel”, which means “confusion”, the site of the confusion of tongues in Genesis 11. Durandus refers the forty-six years of the building of the temple, as stated in John 2, 20, to the post-exilic rebuilding in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah at the end of the 6th century B.C.; historically, the Jews speaking to Christ in the Gospel were referring to the reconstruction under Herod the Great in the first century B.C.)

Again, the fasts were instituted, because in the Old Law, it was commanded to render tithes and first-fruits from all goods to God; wherefore, we must also do the same in regard to ourselves, that is, from our body, our mind and our time. … For indeed, we offer tithes and first-fruits to God when we do good. In Lent a tithe of days is paid, according to Gregory (the Great, hom. 16 in evang., cited by Gratian de consecr. dist. 5, 16). From the first Sunday of Lent until Easter six weeks are numbered, which make 42 days; from these, the six Sundays are removed from the fast, and there remain 36 days of abstinence, which are almost a tenth of the year. Therefore, in order that the number of forty day in which Christ fasted may be fulfilled, four days are recovered in the previous week… To the thirty-six days which are the tithe, four are added … the first of which is a day of sanctification and cleansing, for then do we purify the soul and body by sprinkling ashes on our heads. …

But we in Provence (Durandus was bishop of Mende in the Occitan region of France) begin the Lenten fast on the Monday of the preceding week (i.e. the day after Quinquagesima), and thus we fast two days more than the other nations. This is not only for honesty’s sake, that is, so that being thus purified in these two days, we may begin the holy fast on Wednesday, but also because Lent ends on the great Thursday of the (Lord’s) Supper… Therefore, on the last two days (i.e. Good Friday and Holy Saturday), we fast, not because it is Lent, but because … of the holiness of those days. …

But since in Lent we are invited (to go) through Christ’s fast … and He began His fast immediately after the Baptism, which is (commemorated on) Epiphany, the question arises as to why we begin the fast at this time, and not at the same time in which He fasted, especially since His deeds should be our instruction. There are four reasons for this.

The first is that in Lent we represent the people of Israel, who were in the desert for forty years, and immediately after celebrated the Passover.

The second is that in the spring, men are naturally moved to desire (libido), and fasting was instituted in this period to restrain it.

The third is that the Resurrection is joined with Christ’s Passion; therefore, it was reasonable that our affliction should be joined with the Passion of the Savior. For since He suffered for us, we must suffer along with Him, so that we may finally reign with Him; and after the Passion, the Resurrection follows immediately, according to the Apostle’s word, “If we suffer, we shall also reign with him.” (2 Tim. 2, 12) Likewise, a sick man is more afflicted (by his illness) when he is getting healthier.

The fourth reason is that just as the children of Israel afflicted themselves before they ate the lamb, and ate wild, that is, bitter lettuce, (Exodus 12, 8, from

the Epistle of the Mass of the Presanctified on Good Friday) so also we, through the bitterness of penance, must first be afflicted, so that immediately after we may worthily eat the Lamb of life, that is, the body of Christ, and so mystically receive the Paschal sacraments.

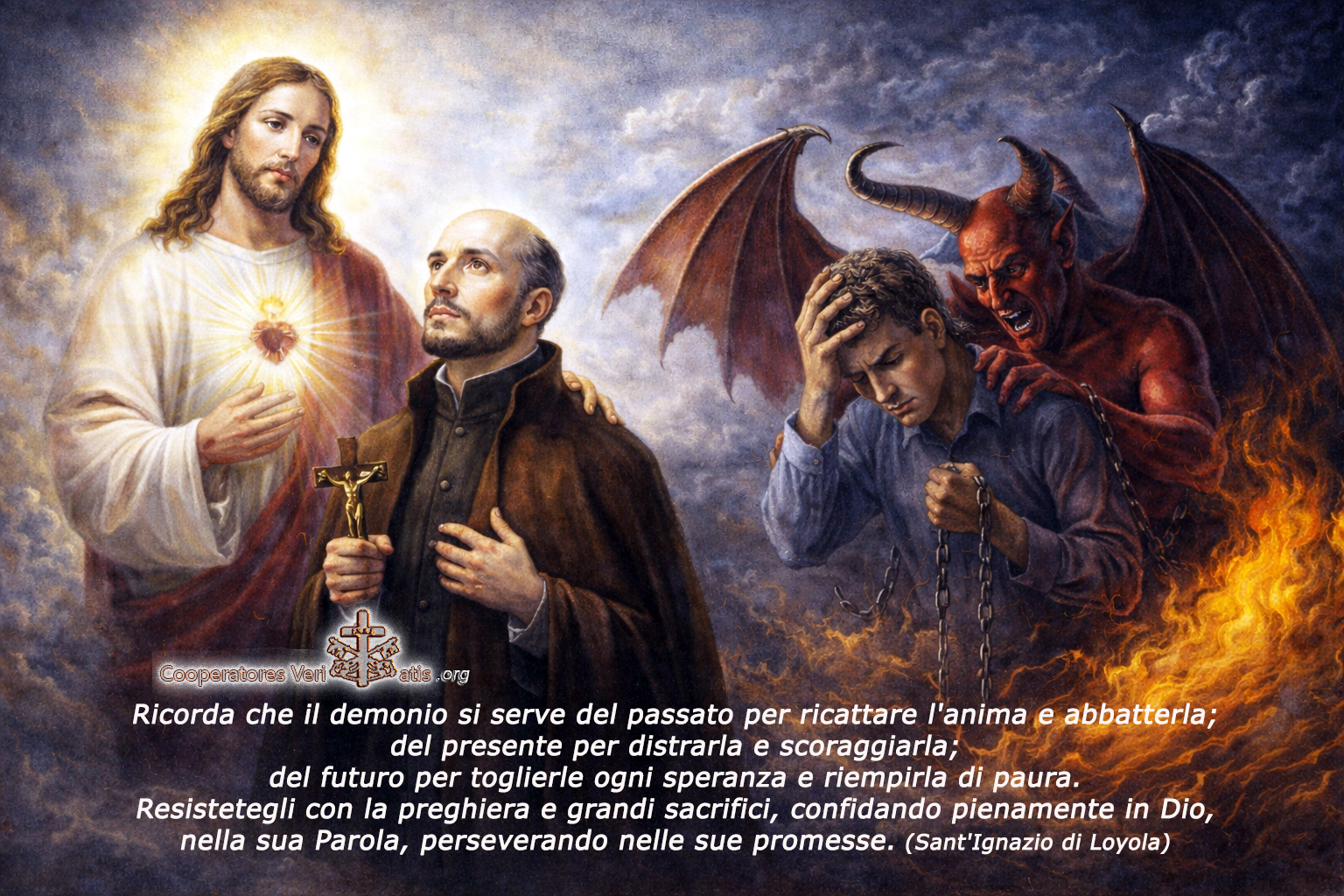

Now in the Lenten Masses, “Bow (humiliare) your heads to God” is often said, since in that period the devil attacks us even more; for which reason, we must humbly pray God, and humble ourselves before him, …

The prayer over the people (at the end of the Lenten ferial Masses) is also said after “Bow (your) heads”, because of the holiness of the season, and to indicate that in this life, prayer must be offered for us, that in the future we may merit to hear, “Come, ye blessed of my Father etc. (Matthew 25, 34, from the Gospel of the first Monday of Lent.) This prayer takes the place of Holy Communion. For once upon a time, all communicated and the deacon would invite those who were to receive communion to kneel; but now, because many receive the Lord’s body unworthily, in place of Communion we use a prayer, and the deacon fulfills his office as before, saying “Bow your heads to God”, because whosoever humbleth himself shall be exalted (Matthew 23, 12, from the Gospel of the second Tuesday of Lent), and whoever is blessed by good deeds in this life, will be deputed to eternal blessing afterwards. In this prayer, therefore, the priest commends the soldiers of Christ to the fight, to combat the ancient enemy and snares of the enemies, and so he first arms them through his minister (the deacon) with the weapons of humility, saying “Bow your heads to God”. And thus at last, when they have bowed their heads, he pours the protection of his blessing upon them, strengthening them, as it were …

(In many medieval Uses, “Oremus. Flectamus genua. Levate” were said before the Collect of every ferial Mass in Lent, not just on the Ember Days as in the Roman Use. This custom is still kept by the Dominicans, who say it in addition to, not in place of, “Dominus vobiscum etc.”) At the first Collect we kneel in accord with the struggle of the present life, representing the affliction of labor and continence; but at the last prayer, which is for thanksgiving, we bow the head, by which is designated humility of the mind, because in the life eternal, every labor will be excluded, but humility will always remain. …

Now in these days the Church, being set in the great struggle of Lent, frequently repeats the Psalm "He that dwelleth", because this psalm tells those who are in a struggle to place their hope in the Lord, and seek all their help from him. (This is Psalm 90, from which are taken all the propers of the Mass of the First Sunday, and the versicles and short responsories of the Office.) …

Also, from Ash Wednesday until Palm Sunday the preface of the fast is said every day, and in some places, even on Sunday. But on Palm Sunday and the following days is said the Preface of the Passion. But it seems to be incongruous that the preface of the fast should be sung on Sundays, since one does not fast on those days, and therefore some people say the daily preface on those Sundays. But even though they are not counted as fast days, they are kept as a fast in the kind of food that is eaten, which is like that of the other days.

(Concerning the anticipation of Vespers on ferial days) … it must be noted that the season of Lent is a time of mourning and penance; but while the penitents are converted to Christ, they pass from darkness to light. Now the evening, because of the failing of the light and the (ensuing) darkness, signifies imperfection. Therefore, because the penitents are pressing forward, not towards imperfection and failure, but rather towards perfection and the light of truth, in regard to Vespers the aforementioned time of light is appropriately anticipated, according to a decree of the Council of Chalon. (Cited by Gratian, de consecr., dist. 1, 50) Vespers are thus said immediately after Mass, though they are otherwise wont to be said close to the night-time.