Here is a timely, 17 minute homily by Father Jay Scott Newman of Charlotte on the connection between heresy, sexual perversion and sexual abuse today.

Below is the Plinthos transcript of this homily which should be preached--even verbatim--by every priest of the world during this golden jubilee of the landmark encyclical Humanae Vitae on the true meaning of Marriage and marital love, the double and inseparable meaning of the marital act: procreation and unity. The integrity of the marriage itself is destroyed when the primary end of marriage, procreation, is thwarted.

Father Jay Scott Newman

Humanae Vitae Homily

Sunday July 29th 2018

17th Sunday in Ordinary Time (B)

Fifty years ago last Wednesday, Pope Paul the Sixth published an encyclical letter on the transmission of human life, known commonly by the first two words of the Latin text, Humanae Vitae.

Everyone knows, or thinks [he] knows, that this letter was written to resist the sexual revolution by declaring the use of birth control pills to be immoral, even for married couples. But very few people have actually read the full text of that letter. So I encourage you to look up Humanae Vitae online this week, and read the short text in one sitting, a task which will take only a few minutes.

Humanae Vitae is a brief statement of the Church’s belief that the revealed Word of God teaches us the full truth about love, marriage and sexuality; and in the context of that revelation, the Church has always known that it is contrary to human dignity and to the purposes of marriage, to attempt to have sexual intimacy, while also intending to prevent the possibility of conceiving a child. For this reason, the use of any means to prevent the conception of a child, including chemicals or sterilization, is always immoral, so too is the use of abortion, whether by chemicals or surgery, to prevent the birth of a child who is already conceived.

But Pope Paul did not simply restate the Church’s ancient and unchangeable teaching, on the beauty, dignity and full meaning of sexual love. No, he also described the consequences for any culture which rejects the truths that are woven into our nature by the Creator, truths that are accessible to right reason, and confirmed by divine revelation. The Pope predicted that a contraceptive mentality, if it ever took hold in a culture, would lead inexorably to an increase in adultery and divorce, the weakening of family life, a general increase in sexual immorality, a reluctance to have children, and an assault on the dignity of women, who would be reduced for too many men from life-long partners in a sacred covenant of love, to objects of sexual desire to be used and discarded, as lust waxes and wanes. In other words, in 1968 Pope Paul the Sixth foresaw the #MeToo moment in our debauched culture, along with all the other sexual confusions of the past fifty years, and the holocaust of contraception and abortion, which is now reaching the level of a civilization-ending catastrophe.

When Humanae Vitae was published in 1968 the Western world was on fire, and almost no one payed attention to the Pope. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy had both been murdered that Spring. Race riots had convulsed many of our great cities, including Washington, Baltimore and Chicago. The streets of Paris were burning with the fevers of revolution and with the violence that always attends such eruptions. The campuses of our elite universities were aflame with protests and the rhetoric of Marxist insurrection. And, three weeks after the publication of Humanae Vitae, the nation watched in horror as the democratic national convention in Chicago descended into a miasma of chaos, incoherence and violence. In other words, the attention of the world was not focused on the small papal encyclical that appeared in July 1968, except, that is, for one odd part of the story. The world, you see, did notice that the Pope’s teaching was immediately rejected as false by no small number of Catholic priests and theologians, many of whom had not actually read the letter before they denounced it in public proclamations. Revolution had come not just to our universities and city streets but to the Church. And the content of Pope Paul’s letter was lost in the storm which was unleashed by the spectacle of priests telling their people to disregard the solemn teaching of the Church, too often with the silent consent of their bishops.

For the past several weeks, in anticipation of this anniversary, I had planned to preach today about all of this as a prelude to explaining what the Church actually does teach about marriage, sexual intimacy and openness to the gift of children. But then, two weeks ago, news broke about the grotesque personal sins of Theodore McCarrick, a now disgraced former archbishop of Washington. What an odd coincidence that the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Humanae Vitae should take place even as one of the most influential American bishops of our time is unmasked as a serial predator and abuser who for several decades continued to rise ever higher in the Church even as he committed grave sins against boys and young men entrusted to his care as a pastor, a shepherd of Christ’s flock, a successor of the apostles, and a cardinal pledged to shed his blood in defense of the Church. If you’ve been following it you know that the story of McCarrick’s crimes is sickening and almost beyond comprehension. But, even worse than this man’s personal atrocities, is the failure of other bishops to decry his sins and the damage he has done. Most bishops simply have not spoken, and too many of those who have, sounded more like liability lawyers or company spokesmen protecting their interests than like the prophets and apostles who denounce unrighteousness and call God’s people to repentance and conversion, contrition, confession and amendment of life.

As you saw three weeks ago at my silver jubilee, I believe that the priesthood is a beautiful and essential gift to the Church. And, I believe that celibacy should remain a permanent part of that gift in the Western Church. But, the truth is that the clerical culture in which priests and bishops live is in many ways diseased and deformed, and must be made new by the fire of divine love, and the truth of the Word of God.

I have now stood in this pulpit for seventeen years, and, week after week, despite my own grave sins, I have done my best to proclaim and explain the gospel of Jesus Christ, including the hard sayings that so many of us have difficulty hearing and accepting. In our time, of course, many of those hard sayings concern sexuality, marriage and family life. But the task of every preacher is to proclaim the gospel in season and out, to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable, and to call the Church to fidelity to God’s revealed Word. In fulfilling that duty here I have never been surprised at the opposition to this task by “the world,” meaning, that part of creation which is in rebellion against the Creator and His eternal plan for our salvation. In fact, a preacher expects opposition to the gospel from the world. But what is not expected is opposition to the gospel from pastors of the Church, most especially from Her bishops, and least of all from members of the sacred college of cardinals. This is among the many reasons why the treason of Theodore McCarrick is a damnable abomination. But while McCarrick’s sins are appalling, they are merely the crimes of one man, a man who is a sinner like all of us, and who is called to conversion, and may yet, we pray, repent and find redemption from his sins in Jesus Christ.

Worse, however, than the sins of one man is the systemic corruption of priests and bishops who do not believe what the Church teaches but continue to preach anyway. They swear at their ordination to teach the gospel as it has been revealed by God and transmitted in the Church, but then with a wink and a nudge they encourage cynical disregard for the revealed truth of God’s eternal Word and create a new religion of their own devising, a faith that will not disturb the indulgence of their ambition and lust and which encourages the people of God to disregard the solemn and sacred truths about love, marriage, sex and the gift of children. In retrospect, I should not have been surprised that the fiftieth anniversary of Humanae Vitae would be interrupted by the obscenities of a fallen bishop which would bring scandal to the universal Church and encourage derision of the priesthood around the world. No. The sorry tale of bishops and priests who harm others by false doctrine or evil conduct, or both, is summed up in the miserable life of Ted McCarrick, and helps explain better than I ever could have, how and why the beautiful truth taught by Pope Paul VI fifty years ago was rejected by so many people, even within the Church.

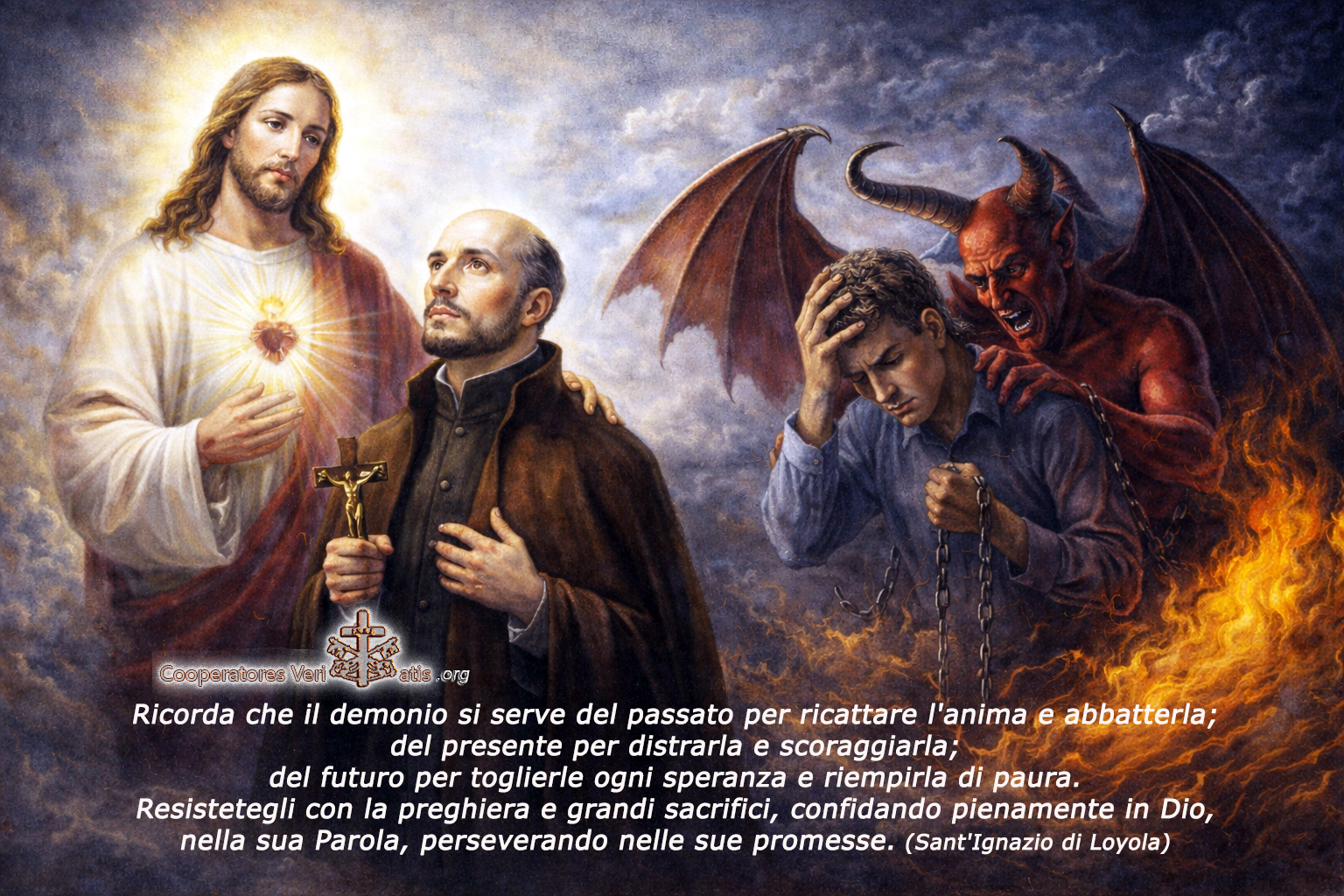

I expect that in the weeks ahead there will be more misery, more stories in the press, more accusations of misconduct by the clergy, and it will all be sickening. But, while the filth continues to spill out, we must all cry out with Saint Paul, “I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, for in it the righteousness of God is revealed through faith for faith, as it is written: ‘he who through faith is righteous shall live.’” But, while we are never ashamed of the gospel, we should always expect shame to accompany the disclosure of the sins of bishops and priests. And we must be mindful that the only one who profits from those shameful sins is the Father of Lies. Strike the shepherd, scatter the sheep. Discredit the messenger and you discredit the message! That is the strategy of our ancient Enemy, the fallen one, who does not want us to hear and heed the Word of God. But friends we are at war, war with principalities and powers, and we must not be deceived by Satan’s lies.

In the midst of this carnage there was a little good news from Rome yesterday. Pope Francis accepted the resignation of Ted McCarrick from the college of cardinals and imposed on him a hidden life of prayer and penance while the charges against him are reviewed and the Pope decides what to do with him. I hope that McCarrick will be laicized, or, as the press usually puts it, “defrocked,” and that every bishop whose advancement he promoted will be scrutinized to ensure that this disease does not spread. But, whatever may happen to this wretched man, and those like him, we should make plans right now for what we can do to help heal and reform the Church. As the scriptures for today’s Mass teach us, what we have to offer is never enough. But, with God’s grace there is always more than a sufficiency to meet our needs. And so, here’s what I suggest.

First, we should read Humanae Vitae, this week, and then change whatever in our lives must be changed to live according to God’s plan for marriage and sexuality.

Second, we should study part three of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, called, “Life in Christ.” Part three includes a concise explanation of each of the ten commandments and places the drama of our moral choices directly in the center of living a virtuous life of grace through faith in the Son of God.

Third, we should go to Mass every Sunday, and, when possible, every day. “Do this in memory of me,” the Savior commanded. And, when we fulfill that commandment by receiving the most holy Eucharist worthily, we are strengthened by God’s grace to live the law of love through an authentic gift of self.

Forth, we should go to Confession regularly, probably about once each month, and subject our lives to a ruthlessly honest examination of conscience in the light of God’s revealed Word.

And finally, we should pray for those, all those, who stumble and fall, including Ted McCarrick. “All men have sinned, and are deprived of the glory of God.” This is the heart of the gospel. And this is why we need a Savior. And, while the sins of the clergy should always disappoint us, they should never surprise us. After all, even those who have been justified by grace through faith in Jesus Christ discover that the mystery of lawlessness remains strong and active in our hearts. And that is why “we do the evil we should not,” and why “we do not do the good we should.” My friends, “ecclesia semper reformanda et purificanda.” The Church is always in need of being reformed and purified, because everyone in the Church is a sinner in need of being reformed and purified, including priests and bishops, starting with priests and bishops. Starting, in fact, with me.

This October, Blessed Pope Paul the Sixth will be canonized, acknowledged as being now among the saints and angels who worship the Lamb once slain who lives forever. And Pope Paul’s prophetic words remain a sure path through the wreckage of the sexual revolution to a life of authentic and fruitful love, a life made possible by grace through faith in God the Son.

On the fiftieth anniversary of Humanae Vitae God be praised for His infinite mercy, for His unconditional love, for His redeeming grace, and for the freedom from sin and the grave revealed by the death and resurrection of the Son of Mary, the Word made flesh, the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the One Who is, Who was and Who is to come, the Lord Jesus Christ.

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Humanae Vitae Revisited -Professor Roberto de Mattei

Professor Mattei says that the denial of procreation as the primary end of marriage is a serious mistake which comes from political correctness and contradicts divine revelation.

New facts about origins of Humanae Vitae emerge from ‘secret’ Vatican commission

Roberto de Mattei

ROME, July 19, 2018 (LifeSiteNews) — At the beginning of 2017, Pope Francis set up a “study commission” to prepare for the 50th anniversary of Humanae Vitae (July 25, 2018). The existence of this “secret” commission was brought to light some months after by two Catholic publications, Stilum Curae and Corrispondenza Romana.

The commission, coordinated by Monsigno Gilfredo Marengo, was tasked with finding in the Vatican archives the documentation relating to the preparatory work on Humanae Vitae which took place during and after Vatican Council II.

The first fruit of this work is the volume by Monsignor Gilfredo Marengo, The birth of an Encyclical. Humanae Vitae in the light of the Vatican Archives [La nascita di un’Enciclica. Humanae Vitae alla luce degli Archivi Vaticani], published by the Libreria Editice Vaticana. Other publications perhaps will follow and other documents presumably will be submitted, privately, to Pope Francis.

From a historiographical point of view, Monsignor Marengo’s book is disappointing. On the genesis and consequences of the encyclical Humanae Vitae, within the context of the contraceptive revolution, the best book, to my view, is Renzo Puccetti’s, The Poisons of Contraception [I veleni della contraccezione] (Dominican Edizioni Studio, Bologna 2013).

Monsignor Marengo’s study does, however, contain some new elements. The most relevant is the publication of the complete text of an encyclical De nascendi prolis (pp. 215-238), which, after five years of agonizing work, Paul VI approved on May 9, 1968, fixing the date of its promulgation for the Solemnity of the Ascension (May 23).

The encyclical that Monsignor Marego defines as “a rigorous pronouncement of moral doctrine” (p.194), was already printed in Latin when there was an unexpected turn of events. The two French translators, Monsignor Jacques Martin and Monsignor Paul Poupard, expressed strong reservations about the document’s overly “traditional” approach. Paul VI, disturbed by the criticism, worked personally on numerous modifications of the text, changing above all its pastoral tone, which became more “open” to the cultural and social demands of the modern world.

Advertisement

Two months later, De nascendi prolis was transformed into Humanae Vitae. The Pope’s concern was to ensure that this new encyclical “would be accepted in the least problematic way possible” (p. 121), thanks not only to the reformulation of its language, but also to the devaluation of its dogmatic character (p. 103).

Monsignor Marengo recalls that Paul VI did not accept the invitation of the Archbishop of Krakow, Karol Wojtyla, to issue a “a pastoral instruction reaffirming, in no uncertain terms, the authority of the doctrine of Humanae Vitae, in face of the widespread protest movement against it” (p. 128).

The objective, or at least the result of Monsignor Marengo’s book, seems to be that of relativizing Paul VI’s encyclical, which is presented as a phase in a complex historical journey that has not been concluded by the publication of Humanae Vitae, or with the discussions that followed it. One cannot “claim to have said the ‘last’ word and to close, if it were ever needed, a decades-long debate” (p.11).

On the basis of Monsignor Marengo’s historical reconstruction, the new theologians who refer to Amoris laetitia will say the teaching of Humanae Vitae has not changed, but must be understood as a whole, without limiting oneself to the condemnation of contraception, which is only one aspect of it. Pastoral care — it will be added — is the criterion for interpreting a document that reminds us about the Church’s doctrine on the regulation of births, but also about the need to apply it according to wise pastoral discernment. In the final analysis, it is a question of reading Humanae Vitae in the light of Amoris laetitia.

Humanae Vitae was an encyclical that caused great anguish (as Paul VI himself called it) and was certainly courageous. Indeed, the essence of the ’68 Revolution was captured in the saying “it is forbidden to forbid,” a slogan that expressed the rejection of every authority and every law, in the name of the liberation of instincts and desires.

Humanae Vitae, in reiterating its condemnation of abortion and contraception, recalled that not everything is permitted, that there is a natural law and a supreme authority — the Church — which has the right and the duty to protect it. Humanae Vitae, however, was not a “prophetic” encyclical. It would have been so, had it dared to oppose the false prophets of Neo-Malthusianism with the divine words “Be fruitful and multiply.” (Genesis 1:28; 9:27).

Yet it did not do so, because Paul VI, in his fear of coming into conflict with the world, accepted the myth of the demographic explosion, launched in 1968 by Paul Ehrlich’s book, The population bomb. In 2017, Ehrlich himself was invited by Msgr. Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo to reiterate his theories on overpopulation at the conference organized by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. The conference was titled: Biological Extinction. How to save the natural world on which we depend. (February 27 - March 1, 2017).

In his book, the author describes the catastrophic scenarios that the inhabitants of Earth would have to face if measures were not taken to contain population growth. What the encyclical rightly condemns is artificial contraception, but without rejecting the new “dogma” of the necessary reduction in births. Humanae Vitae replaced Divine Providence, which up to that point had regulated births in Christian families, with the human calculation of “responsible parenthood.”

The Magisterium of the Church dogmatically affirms, however, that contraception is to be condemned not only because it is an unnatural method in itself, but also because it is directly opposed to the primary end of marriage, which is procreation. If one does not affirm that the procreative end prevails over the unitive one, one can maintain the thesis that contraception can be lawful when it undermines the “intima communitas” of the spouses.

John Paul II vigorously reaffirmed the teaching of Humanae Vitae, but the concept of conjugal love that spread under his pontificate is at the origin of many misunderstandings. In this regard, I refer to the precise observations of Don Pietro Leone, the pseudonym of an excellent contemporary theologian, in his book The Family Under Attack: A Philosophical and Theological Defense of Human Society (Loreto Publications, 2015).

Advertisement

Over the last 50 years, due also to a misguided conception of the ends of marriage, papal teachings have been disregarded, and among Catholics the practice of contraception and abortion, extra-matrimonial cohabitations, and homosexuality have become widespread. The post-synodal Exhortation Amoris laetitia represents the result of an itinerary that has been a long time coming.

Repeating almost verbatim the words spoken on October 29, 1964 by Cardinal Leo-Joseph Suenens in the Council Hall: “It may be that we have emphasized the word of Scripture, ‘Be fruitful and multiply,’ to the point of leaving in the shadows the other divine word, ‘The two will become one flesh’,” Pope Francis said in Amoris laetitia. “We often present marriage in such a way that its unitive meaning, its call to grow in love and its ideal of mutual assistance are overshadowed by an almost exclusive insistence on the duty of procreation” (n. 36).

Reversing these words, we might say that in recent decades we have almost exclusively emphasized the biblical words, “The two will become one flesh,” to the point of leaving in the shadows the other divine words: “Be fruitful and multiply.” It is also from this word, so rich in significance, that we must again set out towards not only a demographic rebirth, but also a spiritual and moral regeneration of Europe and the Christian West.

This article originally appeared in Italian at Corrispondenza Romana. This translation for LifeSite was done by Diane Montagna.

Humanae Vitae was courageous, but not prophetic: Catholic historian

Diane Montagna

ROME, July 24, 2018 (LifeSiteNews) — Humanae Vitae should be celebrated for upholding the Catholic Church’s ban on contraception and abortion but, at least in one sense, it was not prophetic, a noted Catholic historian has said.

The Catholic Church will mark the 50th anniversary of Paul VI’s 1968 controversial encyclical on Wednesday, July 25th.

In a recent article, Professor Roberto de Mattei discussed new facts that have emerged about the origins of Humanae Vitae, as a result of a “secret” Vatican commission’s investigation of archived documents relating to the preparatory work of the encyclical.

The commission’s findings are chronicled by one of its members, Monsignor Gilfredo Marengo, in a new book titled, The birth of an Encyclical. Humanae Vitae in the light of the Vatican Archives.

Now, in this follow-up interview with LifeSiteNews, Professor de Mattei speaks more in depth about the genesis of Humanae Vitae, explains what magisterial authority it has, and discusses the encyclical’s strengths and weaknesses.

De Mattei argues that Humanae Vitae did not express the Church’s doctrine on the ends of marriage with sufficient clarity. Quoting Pope Pius XII, he explains that the Church has always infallibly taught that procreation is the principal end of marriage:

Advertisement

“The truth is that marriage, as a natural institution, by virtue of the Creator’s will, does not have as its primary and intimate end the personal perfection of the spouses, but the procreation and education of new life. The other ends, inasmuch as they are intended by nature, are not equally primary, much less superior to the primary end, but are essentially subordinated to it. This is true of every marriage, even if no offspring result, just as it can be said of every eye that it is destined and formed to see, even if, in abnormal cases arising from special internal or external conditions, it will never be possible to achieve visual perception” (Pope Pius XII, Address to midwives, October 29, 1951).

De Mattei is an Italian historian and president of the Lepanto Foundation. He has taught at various universities and has served as vice-president of the National Research Council, Italy’s leading scientific institution. He is also a member of the recently established John Paul II Academy for Human Life and the Family.

Christian marriage, he says, is aimed ultimately at “giving children to God and to the Church, so that they might be future citizens of Heaven.” Fifty years after the promulgation of Humanae vitae, de Mattei insists that “we need to have the courage to re-examine” the Church’s teaching on the ends of marriage, “motivated only by a desire to seek the truth and the good of souls.”

***

LifeSite: Q. Professor de Mattei, on July 25, 1968 Paul VI promulgated the encyclical Humanae Vitae. Fifty years later, what is your historical judgment on this event?

De Mattei: Humanae Vitae is an encyclical of great historical importance, because it recalled the existence of an immutable natural law at a time when the benchmark for culture and customs was a denial of lasting values amid historical change. Paul VI’s document was also a response to the ecclesiastical revolution that attacked the Church from within after the close of the Second Vatican Council. We must be grateful to Paul VI for not yielding to extremely strong pressure from media and ecclesiastical lobbies that wanted to change the teaching of the Church in this regard.

Q. Unlike many people today, you claim that Humanae Vitae was not a prophetic document. Why?

In common parlance, prophetic is defined as the ability to foresee future events in the light of reason illumined by grace. In this respect, during the years of the Second Vatican Council, the 500 Council Fathers who demanded that communism be condemned were “prophets” in their prediction that this “intrinsic evil” would soon collapse. Those instead who opposed this condemnation — in the conviction that communism contained something good and would last for centuries — were not “prophets.”

In those same years, the myth of the demographic explosion was spreading, and everyone was talking about the need to reduce the number of births. Those like Cardinal Suenens, who asked that contraception be authorized in order to limit births, were not prophets; while Council Fathers like Cardinals Ottaviani and Browne, who opposed such requests by recalling the words of Genesis: “Be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 1:28), were prophets.

The problem facing the Christian West today is certainly not one of overpopulation but of demographic collapse. Humanae vitae was not a prophetic encyclical, because it accepted the principle of controlling births in the form of “responsible parenthood,” even though it was a courageous document in reiterating the Church’s condemnation of contraception and abortion. In this respect it deserves to be celebrated.

Q. Some have suggested that Humanae Vitae offered a new teaching in recalling the inseparability of the two ends of marriage, the procreative and the unitive, and put these ends on an equal footing? Do you agree?

The inseparability of the two ends of marriage is part of the doctrine of the Church, and Humanae Vitae rightly recalls this. However, in order to avoid any misunderstanding, we have to remember that there is a hierarchy of ends. According to doctrine of the Church, marriage is, by its very nature, a juridical-moral institution elevated by Christianity to the dignity of a Sacrament. Its principal end is the procreation of offspring, which is not a simple biological function and cannot be separated from the conjugal act.

Indeed, Christian marriage is aimed at giving children to God and to the Church, so that they might be future citizens of Heaven. As Saint Thomas teaches (Summa Contra Gentiles 4, 58), marriage makes the spouses “propagators and preservers of spiritual life, according to a ministry at once corporal and spiritual,” which consists in “generating offspring and educating them in divine worship” (Eph. 5: 28). Parents do not directly communicate supernatural life to their children, but must ensure its development by passing on to them the inheritance of faith, beginning with baptism. For this reason, the principal end of marriage also involves the education of children: a work — as Pius XII affirms in an address on May 19, 1956 — which by its scope and consequences far surpasses that of generation.

Q. What magisterial authority does Humanae Vitae have?

In an attempt to soften the doctrinal clash with Catholics advocating contraception, Paul VI did not want to attribute a definitive character to the document. But the condemnation of contraception can be considered an infallible act of the ordinary Magisterium, where it reaffirms what has always been taught: any use of marriage in which, using artificial methods, the conjugal act is prevented from procreating life, violates the natural law and is a grave sin. The primacy of the procreative end of marriage can also be considered an infallible doctrine of the ordinary Magisterium, since it was solemnly affirmed by Pius XI in Casti connubii and reiterated by Pius XII in his foundational Address to midwives on October 29, 1951 and in many other documents.

In fact, Pius XII states clearly: “The truth is that marriage, as a natural institution, by virtue of the Creator’s will, does not have as its primary and intimate end the personal perfection of the spouses, but the procreation and education of new life. The other ends, inasmuch as they are intended by nature, are not equally primary, much less superior to the primary end, but are essentially subordinated to it. This is true of every marriage, even if no offspring result, just as it can be said of every eye that it is destined and formed to see, even if, in abnormal cases arising from special internal or external conditions, it will never be possible to achieve visual perception.” The Pope at this point recalls that the Holy See, in a public decree by the Holy Office, “proclaimed that it could not accept the opinion of some recent authors who denied that the primary end of marriage is the procreation and education of offspring, or who teach that the secondary ends are not essentially subordinated to the primary end, but are on an equal footing and independent of it” (S.C. S. Officii, I April 1944 - Acta Ap. Sedis vol. 36, a. 1944 ).

Q. You note in your article that one of the new elements included in Monsignor Marengo’s book is the complete text of the first draft of the encyclical, which was titled De nascendi prolis. You also note how, through a series of events, this encyclical was transformed into Humanae Vitae. Can you tell us more about how this transformation occurred?

The history of Humanae Vitae is complex, and it caused great anguish. The beginning of this story is the Council Fathers’ rejection of the preparatory schema on family and marriage, drawn up by Vatican II’s preparatory commission and approved by John XXIII in July 1962. The chief architect of the turning point was Cardinal Leo-Joseph Suenens, the Archbishop of Brussels, who had a profound influence on Gaudium et Spes and “piloted” the ad hoc commission on birth control established by John XXIII and enlarged by Paul VI.

In 1966, this commission produced a text in which the majority of experts expressed their support for contraception. The following two years were controversial and confusing, as the new documents published by Monsignor Gulfredo Marengo confirm. The majority opinion, announced by the National Catholic Reporter in 1967, was countered by a minority opinion opposing the use of contraceptive methods. Paul VI then appointed a new study group, directed by his theologian, Monsignor Colombo.

After much discussion, they arrived at De nascendi prolis. But then another unexpected turn of events occurred, because the French translators expressed strong reservations about the document. Paul VI made new modifications, and finally, on July 25, 1968, Humanae Vitae was published.

The difference between the two documents was that the first was more “doctrinal,” while the second had a more “pastoral” character. According to Monsignor Marengo, they felt “the wish to avoid that the search for doctrinal clarity be interpreted as insensitive rigidity.” The traditional doctrine of the Church was confirmed, but the doctrine on the ends of marriage was not expressed with sufficient clarity.

Q. In your article, you write that John Paul II “vigorously reaffirmed the teaching of Humanae Vitae, but the concept of conjugal love that spread under his pontificate is at the origin of many misunderstandings.” Can you say more about this?

I am grateful to John Paul II for his clear reaffirmation of moral absolutes in Veritatis splendor. But John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, which is partly taken up by the new Code of Canon Law and the New Catechism, expresses an understanding of marriage centered almost exclusively on spousal love. After fifty years, we need to have the courage to re-examine this question objectively, motivated only by a desire to seek the truth and the good of souls. The fruits of the new pastoral ministry are there for all to see. Contraception is widespread in the Catholic world, and the justification given for it is a distorted view of love and marriage. If the hierarchy of ends is not established, we risk doing precisely what we wish to avoid; namely, creating tension and conflict and, ultimately, a separation of the two ends of marriage.

Q. But isn’t the marriage bond also a symbol of Christ’s intimate union with the Church?

Certainly, but St. Paul’s famous expression (Eph. 5: 32) is almost always applied to the conjugal act, while married love is not only emotional, affective love, but first and foremost rational love. Rational love, elevated by charity, becomes a form of supernatural love and sanctifies marriage. Emotional, sensitive love can be degraded to the point of considering the person of one’s spouse as an object of pleasure. This risk can also arise from an overemphasis of the spousal character of marriage.

Moreover, referring to the image of Christ’s union with his Church, Pius XII states: “In both the one and the other the gift of self is total, exclusive, irrevocable: in both the one and the other the groom is the head of the bride, who is subject to him as to the Lord (cf. ibidem, 22-33); in both the one and the other the mutual gift becomes the principle of expansion and source of life” (Address to newlyweds, October 23, 1940). Today the emphasis is placed only on mutual self-giving, but there is silence about the fact that the man is the head of his wife and family, just as Christ is the head of the Church. The implicit denial of the primacy of the husband over the wife is analogous to the omission of the primacy of the procreative end over the unitive. This introduces into the family a confusion of roles whose consequences we are witnessing today.

Friday, July 27, 2018

Catholic Bishops Beg for a Clear Policy against Evil

By MICHAEL BRENDAN DOUGHERTY

NATIONAL REVIEW

July 26, 2018 6:30 AM

Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley at the Vatican in 2013. (Max Rossi/Reuters)

Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley at the Vatican in 2013. (Max Rossi/Reuters)

NATIONAL REVIEW

July 26, 2018 6:30 AM

Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley at the Vatican in 2013. (Max Rossi/Reuters)

Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley at the Vatican in 2013. (Max Rossi/Reuters)

Leading churchmen are denying the undeniable.

A few cardinals have roused themselves to respond to the month-old press disclosures that Cardinal Theodore McCarrick is a pederast, whereas before he was merely well known as a serial sexual harasser. Their response is depressing in the extreme and should make any Catholic or person of good will wish for their immediate, tearful confessions of fault, and their resignations of high ecclesial office.

Before mainstream media outlets finally reported on his lewd and criminal behavior, McCarrick was the face of the American episcopacy’s response to the sex-abuse crisis in 2002. His lewd behavior with seminarians was an open secret among priests and informed laity. Expert witnesses in priest-abuse cases, such as Richard Sipe, had long ago publicized what they knew of the behavior of “Uncle Ted.” A concerned group of laity and clerics pleaded their case against him in Rome before his elevation to the College of Cardinals. Churchmen across the country who didn’t call him “Uncle Ted” with affection or disgust had another nickname related to his proclivities: “Blanche.”

A few cardinals have roused themselves to respond to the month-old press disclosures that Cardinal Theodore McCarrick is a pederast, whereas before he was merely well known as a serial sexual harasser. Their response is depressing in the extreme and should make any Catholic or person of good will wish for their immediate, tearful confessions of fault, and their resignations of high ecclesial office.

Before mainstream media outlets finally reported on his lewd and criminal behavior, McCarrick was the face of the American episcopacy’s response to the sex-abuse crisis in 2002. His lewd behavior with seminarians was an open secret among priests and informed laity. Expert witnesses in priest-abuse cases, such as Richard Sipe, had long ago publicized what they knew of the behavior of “Uncle Ted.” A concerned group of laity and clerics pleaded their case against him in Rome before his elevation to the College of Cardinals. Churchmen across the country who didn’t call him “Uncle Ted” with affection or disgust had another nickname related to his proclivities: “Blanche.”

American bishops now facing questions about what they knew and when have had to choose between looking clueless or complicit. So far, they are choosing the former. They are not, however, very persuasive in presenting themselves as ignorant of the rumors.

So let’s review what these churchmen have said and ask some questions about their responses to these “revelations.”

First, there is Cardinal Kevin Farrell, who was a protégé of Cardinal McCarrick’s. Farrell shared an apartment with McCarrick for six years, years in which settlements were being paid out in New Jersey for McCarrick’s misdeeds. In a brief interview, Cardinal Farrell said, “I was shocked, overwhelmed; I never heard any of this before in the six years I was there with him. . . . I worked in the chancery in Washington and never, no indication, none whatsoever.” He didn’t mention his living arrangements. But nothing in Cardinal Farrell’s deportment suggests shock, disgust, or embarrassed bewilderment. His expression is one of a man getting through an unpleasant and official line on his actions.

So let’s review what these churchmen have said and ask some questions about their responses to these “revelations.”

First, there is Cardinal Kevin Farrell, who was a protégé of Cardinal McCarrick’s. Farrell shared an apartment with McCarrick for six years, years in which settlements were being paid out in New Jersey for McCarrick’s misdeeds. In a brief interview, Cardinal Farrell said, “I was shocked, overwhelmed; I never heard any of this before in the six years I was there with him. . . . I worked in the chancery in Washington and never, no indication, none whatsoever.” He didn’t mention his living arrangements. But nothing in Cardinal Farrell’s deportment suggests shock, disgust, or embarrassed bewilderment. His expression is one of a man getting through an unpleasant and official line on his actions.

Farrell was also once a senior figure in the Legionairies of Christ, led by sexual abuser, bigamist, and pederast Marcial Maciel. Farrell left, he’s said, over differences in philosophy. What a life! To have been twice put in the best place to know what, at that level, “everyone knows,” and yet to have known nothing. Why should such a clueless man be elevated to the office of cardinal and given a curial position? Why should a prelate whose sense of the Church is so deficient that he resoundingly declared of the abuse crisis in 2002 that it was “over” be in charge of the World Meeting of Families in Dublin this year? If anyone comes forward with credible evidence that Cardinal Farrell did in fact know about McCarrick’s relationships with seminarians, will he resign his offices?

Next there is Boston’s Cardinal Sean O’Malley. Yesterday, he issued a long statement about the matter. In part, read:

Next there is Boston’s Cardinal Sean O’Malley. Yesterday, he issued a long statement about the matter. In part, read:

These cases . . . raise up that fact that when charges are brought regarding a bishop or a cardinal, a major gap still exists in the Church’s policies on sexual conduct and sexual abuse. While the Church in the United States has adopted a zero tolerance policy regarding the sexual abuse of minors by priests we must have clearer procedures for cases involving bishops.

In other words, he blames this on a policy that he and his brother bishops wrote to deliberately exclude themselves from accountability in 2002.

He continues:

In other words, he blames this on a policy that he and his brother bishops wrote to deliberately exclude themselves from accountability in 2002.

He continues:

It is my conviction that three specific actions are required at this time. First, a fair and rapid adjudication of these accusations; second, an assessment of the adequacy of our standards and policies in the Church at every level, and especially in the case of bishops; and third, communicating more clearly to the Catholic faithful and to all victims the process for reporting allegations against bishops and cardinals.

Specific actions: adjudication, assessment of standards, and communicating to Catholics a process for reporting allegations. The last implies that the problem with Cardinal McCarrick lies partly with the flock’s inability to bleat correctly while the wolves devour them. This is all bloodless bureaucrat-ese. Bishops knew about McCarrick and chose to do nothing. Confronted with the reality, they do not accept responsibility, they do not promise to boldly confront evil. They cry out for more policies that would help them avoid direct confrontation.

What is most shameful is how Cardinal O’Malley addresses his own state of knowledge. Father Ramsey of New Jersey, a priest in good standing, had written about McCarrick to O’Malley’s office for the Protection of Minors, and he received in return what amounted to buck-passing boilerplate about how offenses against adults aren’t handled by O’Malley’s office.

O’Malley writes of this event:

Specific actions: adjudication, assessment of standards, and communicating to Catholics a process for reporting allegations. The last implies that the problem with Cardinal McCarrick lies partly with the flock’s inability to bleat correctly while the wolves devour them. This is all bloodless bureaucrat-ese. Bishops knew about McCarrick and chose to do nothing. Confronted with the reality, they do not accept responsibility, they do not promise to boldly confront evil. They cry out for more policies that would help them avoid direct confrontation.

What is most shameful is how Cardinal O’Malley addresses his own state of knowledge. Father Ramsey of New Jersey, a priest in good standing, had written about McCarrick to O’Malley’s office for the Protection of Minors, and he received in return what amounted to buck-passing boilerplate about how offenses against adults aren’t handled by O’Malley’s office.

O’Malley writes of this event:

Recent media reports also have referenced a letter sent to me from Rev. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. in June of 2015, which I did not personally receive. In keeping with the practice for matters concerning the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, at the staff level the letter was reviewed and determined that the matters presented did not fall under the purview of the Commission or the Archdiocese of Boston, which was shared with Fr. Ramsey in reply.

Notice how lawyerly this language is. O’Malley says he did not “personally receive” the letter. An interesting bit of rhetoric. On the surface, it allows one to conclude that O’Malley simply never knew about it. But O’Malley does not say whether staff discussed with him the contents of the letter and the contents of his office’s response to the letter. In fact, it is preposterous to believe that a matter so sensitive as grave accusations against one of the most notable churchmen in his country would be handled entirely by staff without his knowledge.

O’Malley’s official reputation, the one he is anxiously guarding, is that he is punctilious about accusations of sexual abuse. His real reputation is one as a zealous micro-manager of his own reputation. O’Malley surely had heard of the rumors about McCarrick’s behavior with seminarians, and he surely knew that McCarrick chose to live his retirement on the grounds of a seminary, where he would have access to young candidates for the priesthood, when his office received these complaints. Did he do anything with the knowledge of the complaint besides send back a form letter washing his hands of the situation? If his judgement allowed him to wave away such a grave situation, what good will better policies do?

Notice how lawyerly this language is. O’Malley says he did not “personally receive” the letter. An interesting bit of rhetoric. On the surface, it allows one to conclude that O’Malley simply never knew about it. But O’Malley does not say whether staff discussed with him the contents of the letter and the contents of his office’s response to the letter. In fact, it is preposterous to believe that a matter so sensitive as grave accusations against one of the most notable churchmen in his country would be handled entirely by staff without his knowledge.

O’Malley’s official reputation, the one he is anxiously guarding, is that he is punctilious about accusations of sexual abuse. His real reputation is one as a zealous micro-manager of his own reputation. O’Malley surely had heard of the rumors about McCarrick’s behavior with seminarians, and he surely knew that McCarrick chose to live his retirement on the grounds of a seminary, where he would have access to young candidates for the priesthood, when his office received these complaints. Did he do anything with the knowledge of the complaint besides send back a form letter washing his hands of the situation? If his judgement allowed him to wave away such a grave situation, what good will better policies do?

My office doesn’t have a policy against plunging hammers into the necks of my colleagues. But my co-workers would not excuse themselves from the duty to stop me from doing this by citing the absence of such a policy in a rulebook, or by explaining that their job description did not explicitly include language about hammer-wielding colleagues. O’Malley is blaming his lack of action on a lack of policy, when the problem is a fear of confrontation, insufficient zeal, or — most likely of all — his moral compromise and passivity in the face of a well-known culture of sexual abuse, blackmail, and moral impunity within the Catholic episcopacy.

He’s not the only one who has to answer tough questions. Cardinal Wuerl said last month that he had reviewed the records of the Washington, D.C., archdiocese. “Based on that review,” he concluded, “I can report that no claim — credible or otherwise — has been made against Cardinal McCarrick during his time here in Washington.”

Some questions for Cardinal Wuerl might go something like this. The Vatican’s representative in Washington, D.C., knew about the legal settlements for McCarrick in 2004; when were you informed of them? If you were informed of these settlements, did you take that into consideration when Cardinal McCarrick requested to live in different seminaries that train priests for your diocese? If you did not know about them, did Bishop Joseph Tobin or his predecessors in Newark have a duty to inform you of them, given McCarrick’s living arrangements? Why, near the end of the last decade, was McCarrick suddenly asked to leave the seminary and reside instead at St. Thomas Woodley Park under Father Roderick McKee?

Some questions for Cardinal Wuerl might go something like this. The Vatican’s representative in Washington, D.C., knew about the legal settlements for McCarrick in 2004; when were you informed of them? If you were informed of these settlements, did you take that into consideration when Cardinal McCarrick requested to live in different seminaries that train priests for your diocese? If you did not know about them, did Bishop Joseph Tobin or his predecessors in Newark have a duty to inform you of them, given McCarrick’s living arrangements? Why, near the end of the last decade, was McCarrick suddenly asked to leave the seminary and reside instead at St. Thomas Woodley Park under Father Roderick McKee?

Further, you are the American on the Congregation of Bishops in Rome. It’s widely reported that McCarrick’s lobbying for certain candidates for elevation in the Church was important. How many times did you receive him for an audience on these matters? What was the weight of his word in your own recommendations for Joseph Tobin, Kevin Farrell, and Blase Cupich? If you knew of these settlements, why did his word have any weight with the congregation and with the Vatican?

I don’t expect answers to these questions. But as a Catholic, I would find it satisfying to at least watch these men squirm or sweat while they lie to us, rather than delivering their lines in great comfort and an atmosphere of deference.

Reporters could also cut to the chase. Do you know of bishops who are sexually active? Are you sexually active? They should dig through the same “everybody knows” rumor mills that had accurate information on Cardinal McCarrick. Ever hear anything funny about Cardinal Edward Egan? About parties that Cardinal Law hosted? About Cardinal Bernadin? What about the reputation of the Mundelein Seminary?

I don’t expect answers to these questions. But as a Catholic, I would find it satisfying to at least watch these men squirm or sweat while they lie to us, rather than delivering their lines in great comfort and an atmosphere of deference.

Reporters could also cut to the chase. Do you know of bishops who are sexually active? Are you sexually active? They should dig through the same “everybody knows” rumor mills that had accurate information on Cardinal McCarrick. Ever hear anything funny about Cardinal Edward Egan? About parties that Cardinal Law hosted? About Cardinal Bernadin? What about the reputation of the Mundelein Seminary?

I don’t expect answers to these questions. But as a Catholic, I would find it satisfying to at least watch these men squirm or sweat while they lie to us.

A spokeswoman for the diocese of Metuchen said that she had spoken to Cardinal Tobin and that he “has expressed his intention to discuss this tragedy with the leadership of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in order to articulate standards that will assure high standards of respect by bishops, priests, and deacons for all adults. ”

An expressed intention to articulate standards endorsing high standards. Let them eat standards. This is the moral imagination and moral vocabulary of Cardinal McCarrick’s peers in the Church. They need new policies to confront predators; the fear of perdition doesn’t move them to do so. Nor does respect for the seminarians or their congregants. Nor does self-respect. The reaction of the cardinals goes some way toward explaining how a man like McCarrick flourished in their ranks.

A spokeswoman for the diocese of Metuchen said that she had spoken to Cardinal Tobin and that he “has expressed his intention to discuss this tragedy with the leadership of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in order to articulate standards that will assure high standards of respect by bishops, priests, and deacons for all adults. ”

An expressed intention to articulate standards endorsing high standards. Let them eat standards. This is the moral imagination and moral vocabulary of Cardinal McCarrick’s peers in the Church. They need new policies to confront predators; the fear of perdition doesn’t move them to do so. Nor does respect for the seminarians or their congregants. Nor does self-respect. The reaction of the cardinals goes some way toward explaining how a man like McCarrick flourished in their ranks.

Thursday, July 26, 2018

Cardinal Theodore McCarrick's Praise of Pope Francis and Credit for His 2013 Election

Instructive to watch in the present Cardinal McCarrick disgrace.

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

"The opinion that contraception is indispensable for the stability and the love of the spouses is a crude opinion, and is irreconcilable with a Christian vision of man." Wojtyła

Letter to Pope Paul VI (1969) Card. Karol Wojtyła Translated by LifeSiteNews Vatican correspondent Diane Montagna

Most Holy Father,

With this letter, I again wish to thank Your Holiness for the encyclical Humanae vitae, whose promulgation in July 1968 concluded a period dedicated to the in-depth study of the theme of the transmission of life in marriage, in light of the principles of Christian morality. During this period, the Church, according to the instructions expressed by her Supreme Master and Shepherd, has been careful not to question this ethical principle, and has continued to proclaim it in this matter. She has also endeavored to gain a deeper understanding of its meaning, raison d'être and possibilities of application in the face of the current state of human science, particularly in the fields of contemporary physiology, psychology and demography. The moral doctrine of the encyclical Humanae vitae was accepted, after its publication, by all the Christian faithful and especially by the Catholic episcopate with great conviction and profound gratitude. Yet, in some areas, the formulation of a clear doctrine in this very important area of human morality has come up against already existing doubts about the principle itself, as well as some different practices present in conjugal life and in pastoral life. There are theologians, including some often quoted by the Church, who still today make themselves the spokesmen of these doubts. Advertising and the means of social communication amplify their circulation and sow confusion in pastoral ministry. Such disorientation creeps in both among the laity — particularly in some circles — and among the priests who are pastors of souls and confessors, despite clear statements by the Holy See and local bishops on this matter. The confusion regards not only the correct discernment of the moral norms contained in the encyclical Humanae vitae and of their binding character, but also the whole of the Christian life. In fact, challenging the moral doctrine of the Church in a field as important as that dealt with by the encyclical can be an occasion that gives rise to a much broader process of challenging other elements of the Christian faith and practices. Therefore, even in societies where faith and moral conscience are such that the Holy Father’s directives are willingly accepted, great difficulties arise due to interpretations of the encyclical Humanae vitae that differ from those of the Pope. Thanks to means of social communication, people from every corner of the world receive information immediately. In particular, statements of some episcopates are used, which are considered different from the teaching of the encyclical, especially with regard to practical solutions. In this situation, it seems to be absolutely necessary that the Holy See contemplate a series of provisions aimed at helping priests and the laity to resolve these difficulties. One could consider drafting a very detailed instruction to priests engaged in ministry — especially confessors, catechists and preachers. This instruction, moreover, should contain very precise positions regarding several theological formulations, especially theological-moral ones, whose tenor is in clear disagreement with the teaching of Christ transmitted by the Church. In doing so, one could clarify the Church’s position with respect to certain theological opinions, whose authors — and their followers — believe that the absence of such a clarification confirms their theses. In particular, it would be necessary to clarify the issue of the obligation and infallibility of the ordinary magisterium of the Popes, and to point out the dependence of the Catholic theologian on the authority of the magisterium of the Church. In this context, I would like to enclose with this letter several more detailed proposals aimed at giving structure to the content of the Pastoral Instruction in question. These proposals were drawn up by the group of theologians and priests in Krakow who, before the publication of the encyclical Humanae vitae, had already prepared a long memorandum on the problems the encyclical would have to address. I sent this memorandum to the Holy See in February 1968. At present, the same group of theologians and priests — including one of the auxiliary bishops of Krakow — has prepared the proposals that I am submitting to Your Holiness. These proposals represent only a general schema. They do not constitute the actual text of the instruction, but indicate the issues that, in our humble opinion, should be addressed.

I The first part of the instruction should contain the statements of Bishops and Episcopates published on the occasion of the encyclical Humanae vitae. This is an immense amount of material, so we need to find the best way to publish it, if we do so in the Instruction in question. Publishing the episcopal statements along with the proposed instruction would show the close link between the teaching of the Holy Father in the encyclical and the teaching of the college of Bishops, which is the same. After the Second Vatican Council, proof of collegiality has acquired unprecedented positive value. In the context of the statements made, it is necessary to highlight some of them which, compared to the whole, involve a number of differences. These include the following (according to the documentation in our possession):

1. Nordic and Scandinavian countries, Pastoral Letter of the Bishops of the Countries of Northern Europe, in the encyclical “Humanae vitae” of Pope Paul VI, 10/10/1968;

2. Federal Republic of Germany, Wort der deutschen Bischöfe zur seelsorgischen Lage nach dem Erscheinen der Enzyklika “Humanae vitae,” dated 8/30/1968

3. France, Note pastorale de l’Episcopat français sur l’encyclique “Humanae vitae,” November 1968

4. Belgium, Déclaration de l’Episcopat belge sur l’Encyclique “Humanae vitae,” 8/30/1968

5. Canada, Déclaration des Evêques canadiens sur l’Encyclique “Humanae vitae” dated 9/27/1968

6. Luxembourg, Bischofswort zum Familiensonntag über die Enzyklika “Humanae vitae” dated 6/1/1969.

In principle, these statements accept the authority of the teaching power of the Pope as well as the entire content of his encyclical. At the same time, however, they seek to take into account the reactions of the laity and priests, that the demands of Christian morality formulated in the encyclical Humanae vitae are “concerning.” This attitude certainly comes from an authentically pastoral anxiety. It is also the manifestation of a psychology of dialogue, which makes us attentive to the thoughts and objections of our interlocutors and urges us to follow them to the limit of what is possible. On the other hand, the situation in recent years, in which the pastoral practice of some regions considered contraception morally acceptable, undoubtedly exerts its influence. We therefore understand the origin of the “concern” or even “surprise” caused by the demands of conjugal morality recalled in the encyclical Humanae vitae. The authors of the aforementioned statements have made themselves the spokesmen for this concern. The reason for these statements is to be found, in most cases, in the concern deriving from the comparison between the moral conscience of the laity and priests and the real demands of Christian morality dealt with in the encyclical. One can observe that the Authors of these documents intend, on the one hand, to maintain the submission of the faithful to the teaching of the Pope, and on the other, to safeguard at all costs the union of the faithful with the Church, seeking to understand their situation and to apply the principles of Christian morality in such a way as to soothe their consciences without, however, having to change the behavior maintained up to now. The instruction we are proposing cannot, of course, keep silent about the difficulties of the problem. In this regard, the statements of the episcopates cited are a help, as they will allow the Instruction to examine in detail the very heart of these difficulties, whether doctrinal, pastoral or simply moral, although one should not concern oneself only with the difficulties or give them first place: the magisterial character of the encyclical Humanae vitae and of the teaching of the Pope undoubtedly indicate this path. (We wish to emphasize the importance not only of extraordinary teaching but also of the ordinary teaching of the Popes). On the other hand, the reaction of “surprise” and “concern” triggered by the appeal to principles of conjugal morality in the encyclical is far from being the general one. It was, in fact, the reaction only in some circles. Probably, it was able to conceal from the eyes of these Episcopates the reaction of other circles, other groups of laity and priests. These were precisely the groups and circles that welcomed Paul VI’s encyclical as the logical expression of Gospel morality, which is naturally very demanding, but which, at the same time, is authentically Christian and authentically human. Many groups have expressed their deep gratitude to the Pope for the teaching contained in the encyclical Humanae vitae. In these circumstances, we wish to reiterate forcefully that the moral law is founded not on the approval or disapproval of men, groups or human circles, but rather on the objective nature of moral good and evil. In the light of this conviction, we are now making the following proposals.

II The second part of the instruction should contain the doctrine of the Second Vatican Council which, following the First Vatican Council, once again defines the principles of infallibility. It would be necessary simply to cite the Constitution Lumen gentium III 25, which states that “This religious submission of mind and will must be shown in a special way to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra; that is, it must be shown in such a way that his supreme magisterium is acknowledged with reverence, the judgments made by him are sincerely adhered to, according to his manifest mind and will. His mind and will in the matter may be known either from the character of the documents, from his frequent repetition of the same doctrine, or from his manner of speaking.” There is also another reason that urges us to take up these texts of Vatican II: the statements of the episcopates in question also refer to this principle (and to the same texts), declaring that they adhere to the encyclical Humanae vitae in a spirit of faith, as it is due to the teaching of the Pope. The encyclical Humanae vitae is not a solemn document of ex cathedra teaching; therefore it does not contain any dogmatic definition. However, since it is a document of the ordinary teaching of the Pope, it has an infallible and irrevocable character. Such a character, in fact, is specifically inherent not only to ex cathedra dogmatic definitions, but also to the acts of the ordinary teaching of the Church (see the quoted passage from Lumen gentium, III 25). As for the encyclical Humanae vitae, its content does not give rise to any doubts about the matter. The Holy Father affirms that the Church’s teaching on the regulation of births does nothing but “promulgate divine law” (Humanae vitae, n. 20). Addressing himself to spouses, the Pope speaks in the name of the Church, which proclaims “the imprescriptible demands of divine law” (HV, n. 25). While inviting priests and moral theologians to adhere unanimously in a spirit of faith to the teaching of the Popes regarding the ethics of married life, the Pontiff affirms that it is a matter of the “saving doctrine of Christ.” (HV, 29). Moreover, he also speaks of the laws inscribed by God in human nature, so as to ensure that spouses conform “what they do to the will of God the Creator. The very nature of marriage and its use makes His will clear, while the constant teaching of the Church spells it out.” An act of mutual love carried out at the expense of the power to transmit life “contradicts both the divine plan, which constitutes the norm of marriage, and the will of the Author of human life [...] and [...] is in opposition to the plan of God and His holy will.” Since he speaks in the name of the Church, the Pope is aware that he is “proclaiming humbly but firmly the entire moral law, both natural and evangelical. Since the Church did not make either of these laws, she cannot be their arbiter—only their guardian and interpreter. It could never be right for her to declare lawful what is in fact unlawful […].” This moral law applied to marriage is imprescriptible. These statements, which present the Pope’s intention in a very clear and incisive way, show that it is impossible to think that the conjugal morality contained in the encyclical Humanae vitae could be revoked, i.e. considered fallible. One cannot even think of accepting the opinion of those who see in the encyclical Humanae vitae only pastoral advice and directives — which would correspond to the educational role of the Church — and even less the opinion of those who want to see in the encyclical only an invitation to open up a debate on the issue of marital life and ethics (the encyclical would open a dialogue in which participants would be, in the name of collegiality, the bishops and the Pope). These views are at odds with the clear and distinctive character of the document. Moreover, they are also harmful, since they imply that because of the revocable and therefore fallible character of the encyclical Humanae vitae, everyone could, depending on the circumstances, form a different opinion, which would be for him the norm of his own actions. It cannot be tolerated that, after the encyclical Humanae vitae, there is a state of uncertainty; in particular, it is not acceptable to affirm that this state of uncertainty is reinforced by the attitude of the Pope himself, since an impartial analysis of the text of Humanae vitae demonstrates the exact opposite. In light of this analysis of the content of the encyclical Humanae vitae, we need to look more deeply at the opinions of those theologians who, in the teaching of the encyclical on conjugal morality — especially on the inadmissibility of contraception — see a revocable and, consequently, fallible teaching. In the eyes of these theologians, only solemn teaching ex cathedra is infallible and irrevocable. The result is such a restriction of the magisterium in the sphere of moral problems as to make it irrelevant, given that extraordinary teaching (ex cathedra) in this type of issue has been used only in very rare cases. It should be noted that these theologians, in their opinions, restrict the competence of the Church’s magisterium in moral questions since they believe that, in the field of morality, judgements are by their very nature unstable and depend on the historically changeable character of human nature itself. They are convinced, moreover, that within the ambit of natural law, the Church’s magisterium cannot issue coercive and definitive decisions, since it is a merely rational sphere of knowledge of man and the condition of his life. They have also called into question the competence of the Church’s magisterium as it would not have been able to see the link between particular norms of Catholic moral doctrine and Revelation. They have therefore challenged certain moral principles taught by the magisterium, justifying this attitude by the fact that these principles are not explicitly found in Sacred Scripture. It would be useful to recall here the general principles enshrined in the First Synod of Bishops of 1967, which define the tasks of theologians in the Church and, in particular, their attitude towards the Magisterium and pastoral ministry.

III The third part should deal with conscience and its relationship to the moral law. Conscience is the decisive and binding norm of human activity: it is binding, since man must act according to his own conscience, and it is decisive, since it constitutes the ultimate and direct element that guides human action. Nevertheless, while fully accepting the normative character of conscience, one cannot see in it the one and only norm, let alone a norm superior to the moral law. Attributing to conscience an autonomy that would give it not only a normative but also a legislative role, would be contrary to the foundations of both natural and revealed ethics. Such autonomy would be tantamount to accepting subjectivism and relativism in morality. Now, subjectivism and relativism are in contradiction with true morality, especially with Christian morality, simply because these amount to the denial of objective moral good and evil and, consequently, of the specific function of conscience. It is, in fact, up to conscience to determine good and evil and to discern it according to the objective moral law. The whole doctrinal tradition of the Church recognizes that the objective moral law is found in Revelation. It also recognizes that Revelation (particularly the Letter to the Romans, 2) affirms the existence of the natural moral law. This affirmation is of great importance for faith and theology, regardless of the different philosophical conceptions of natural law. When the Church, in her teaching of morals, refers to the natural law, she does not allude to any of these philosophical conceptions, but sees the natural law as an object of faith and theology. She regards it to be the foundation of the morality which, in turn, has been explicitly revealed. The specific norms of the moral law are accessible to human reason, which recognizes and accepts them as the foundation of morality. The Church considers herself to be the guardian and teacher of these norms, for, although they were not the object of a special revelation, Revelation nevertheless confirms their existence and their binding force. The essence of the Church’s teaching on natural law consists in emphasizing that there is an objective moral order, which derives from the nature of man, a universal and immutable order, guaranteed by the Supreme Legislator and, consequently, independent of the State and its power. Together with revealed law, this moral order represents the constitutive whole of morality. It falls within the competence of the Church: in fact, its observance is a condition for salvation. This is precisely why Paul VI defines the teaching of the encyclical Humanae vitae as the expression of objective moral truth that no one, not even the Church, can change. The efforts of theologians to provide a new interpretation, or a better (more modern) expression of the issue of natural law, cannot be carried out at the expense of its basic principles, which are founded on Scripture, Tradition and the Magisterium. Thanks to these sources, we know with the same certainty conscience derives its normative force — which is binding and decisive — from objective morality. This law is divine. And if it were human, it would be rooted in a divine law or formally revealed, or contained in natural law. It is precisely this law that Paul VI recalls and explains in the encyclical Humanae Vitae. That said, one cannot consider as morally good the attitude of a Catholic who, fully aware of the moral doctrine of the Church, acts according to the subjective judgment of his own conscience and opposes the norms he well knows. This is the focal point on which the statements of some episcopates fix all their attention, as they try to show maximum indulgence towards the various processes of consciences in this difficult and painful field of human morals. However, the possibility of profoundly erroneous states of consciences cannot be excluded. A distinction must be made between the acceptance of the possibility of such a state of conscience and the acceptance of the subjective right of a Catholic to create such a state, or to form a specific judgment about conscience that would be in disagreement with the objective moral law, invariably taught in the Church through the voice of the Supreme Magisterium. The encyclical Humanae vitae highlights precisely what, in the field of the transmission of life, is a stable law of morality taught by the Church. It concerns responsible parenthood and the ban on contraception. All the circumstances that enable science, culture and technology to develop today allow us to understand anew what is immutable in the divine moral law, without this immutable [law] being changed. Consequently, we must also remember the principles that moral theology uses to describe the way in which a sure and upright conscience is formed. It is achieved by knowing the moral value of an act. Conscience, as such, demands that one refrain from performing an act if, a correct discernment of its moral value has not previously been made. This moral obligation also allows us to clarify the scope and direction of the duties of priests and confessors in this area. They have a duty to teach the moral law in order to make it possible to formulate true judgments of conscience. The formation of consciences is one of the fundamental tasks of the priestly ministry.